by OLIVIA NEAL

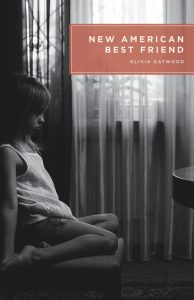

Olivia Gatwood. New American Best Friend.

Button Poetry. March 2017. pp. 60.

“when they call you a bitch, say thank you. / say thank you, very much.”

This is the powerful final line of Olivia Gatwood’s debut book of poetry, New American Best Friend (Button Poetry, 2017). The ending leaves the reader with a feeling of strength that perfectly encapsulates why her work has become very popular in contemporary poetry circles. Gatwood rises above misogynistic reproach with a confidence that is desperately needed, especially now and especially for her young fans.

Gatwood got her start through Button Poetry, a publishing company that emerged from the slam poetry scene and promotes writers who are masters of spoken word. She represents a new generation of writers who get the word out through the annual College Unions Poetry Slam Invitational, open only to college-age poets. She is young, enthusiastic, and brave.

The title of her collection comes from the poem “The Only Thing I Brought From America,” which describes the persona that one of Gatwood’s childhood friends pushed on her, a caricature of American girlhood: rich, suburban, and aloof. But Gatwood knows that she’s not that girl. She says, “we live in the Sunset motel / where I collect snails and eat chicken and ketchup / sandwiches for dinner.” That is what this collection is about: Gatwood’s tenacious rejection of the images that other people ascribe to her. She pushes back against the way people like her friend constrict her experiences with femininity, relationships, and growing up. Her strong voice and imagery guide us through stories of her life that emphasize her unapologetic sense of self, even from an early age.

That same childhood friend calls Gatwood a “dyke” out of spite, because Gatwood’s sportiness gains her attention from boys. But Gatwood tells her own story of developing sexuality and her attraction to girls. In the poem “Like Us,” she describes an early relationship with a girl her age, an honest portrayal of secrecy, guilt, and discovery. “we both felt bad about / the game so we did it on the pull-out / bed, that way, when we were finished / slamming our tiny, moth bodies / against the porch lights of each other, / we could tuck the cot away and / the bedroom would go back to / the way it was before.” It is this story—this moment—that defines the beginnings of her attraction to girls, not the insults from jealous peers who don’t understand her.

Gatwood uses vulnerability as a form of artistic expression. From the beginning of the book, she grapples with intimacy, memory, and budding womanhood in a way that asks readers to understand and identify, even if they have no such experiences. Her snapshots of adolescence are filled with the uncomfortably personal, but she describes them with such acuity and wit that they uncover secrets we all know to be true. The first poem in the collection, “Jordan Convinced Me That Pads Are Disgusting,” confronts us with her first experience with tampons. Her best friend, Jordan, inserts it for her, “on the floor / like a mechanic investigating the underbelly of a car.” She faints from the experience, but that image of familiarity between her and Jordan gives us a sense of Gatwood’s character, and her unwavering commitment to truth. These poems can often be difficult to read, especially for the faint of heart, as they look close at things that we’re often disgusted by. But it’s exactly this instinct that she wants to examine.

By bringing the reader into the consciousness of a young mind, focusing on moments that could be uncomfortable, Gatwood banishes the shame that we expect to accompany these topics. She writes odes to objects and experiences that others would shame her for, choosing instead to celebrate them. This includes her attraction to other girls, such as in “Ode to Elise in Eight Grade Health Class,” where she admits, “I had never pined / so badly for denim / to slip down her lower back.” She writes odes to the word pussy, to her period underwear, to her bitch face, all things that she has been told to feel ashamed of. Through these bold stories, she tells others that their shame is not needed, and conveys hope to young girls who may also fall into these traps.

As the book goes on, her poems age as she explores more recent memories. She uncovers the ugly truths of sex, love, and the body with transparency. In some of these moments, she admits to making herself smaller and to accepting treatment she does not deserve. In “The Ritual,” for instance, she describes a difficult sexual encounter: “you have grown accustomed to discovering all of the ways / you can make the pain intangible. unrecognizable.” Through these poems, we see that Gatwood knows personally the kind of painful love that is asked of women. But later, she draws herself a roadmap for a kind of life without it. Her poem “Alternate Universe in Which I Am Unfazed by the Men Who Do Not Love Me” speaks to women who feel desperate and taken advantage of, and it resonates with anyone who has given too much thought to people who were not worth it. She dreams of a world in which she can say, “i do not beg. i do not ask for forgiveness. i do not hold my breath while he finishes.” While she often writes poems that ask women to be confident and fearless, she doesn’t claim to always embody that ideal. That is her forte as a writer: showing strength through authenticity.

The poems in New American Best Friend use emotion as a guiding light, often at the exclusion of other literary considerations. Gatwood is a performer, first and foremost, and each of her poems is written to be read aloud. When she performs them, she is unapologetic and declaratory. In print, this makes her poems seem conversational, a far stretch from the kinds of classical poetry that preceded her. She doesn’t use line breaks to convey meaning or pauses in the way poets have done historically. Instead, her poems are almost prose-like, with long lines of equal lengths that are meant to be read as one continuous story. Some readers who prefer precision in the way that poetry unfolds on the page may be disappointed by Gatwood’s seemingly haphazard method of converting her spoken word to print. But this stylistic decision speaks to Gatwood’s literary priorities: her roots in performance secure the strong voice of her work. Feelings seep between the lines, creatingcomplete stories that capture a pocket of reality. For a moment, while reading her work, we live in her world. It becomes like worshipping at the altar of adolescent fervor.

Gatwood’s work epitomizes a common method in contemporary poetry: using vivid imagery of a personal moment to illustrate a social tendency. The quiet moments of her life resonate with young women who have felt the way Gatwood is feeling in her poems. This collection crescendos in passion and rebellion, calling to readers who have been hurt, have felt small, have felt vulnerable. You will be pulled into her world, and you will be asked to question the way things are and to consider the way things could be.