by KATHARINE COLDIRON

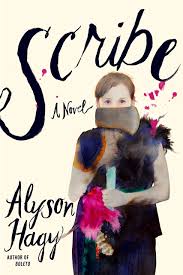

Alyson Hagy, Scribe (Graywolf Press, October 2018), pp. 176

It’s unclear where or when we are at the start of Scribe, a slim novel that maps an extraordinary range of human cruelty. The awful, scraping life led by the characters in the aftermath of war and disease could be postapocalyptic, some fantasy of survival in a Montana of the distant future, or it could be postbellum, the crazed and desperate days of the mid-1860s in the defeated South. The book’s author, Alyson Hagy, hails from the Blue Ridge region of Virginia (where this reviewer also spent some of her childhood), and the idiom and landscapes of the novel do resemble that area. But the novel never specifies. Time and place are not important to Scribe; the deals people make with each other and with themselves, and the tangled connections between transcription, preservation, and power, matter more.

Plot is not the point of such a language-dependent novel, but what plot exists links characters in a chain of terrible bargains—bargains stretching from the unnamed female narrator to the man, Hendricks, who employs her to write a letter for him, to the villainous Billy Kingery, to his many spies, to the neighbors who object to the narrator on principle, to the narrator again, to her dead sister. “We all owe,” the narrator says. The novel’s driving conflict is a power struggle that the narrator would be happy to opt out of entirely, as long as she can continue to barter her ability to write letters for more practical needs and remain in her house. But the house is her only node of power, and it’s power that someone else wants. Revealing more of the plot’s mechanics would give away some of the overwhelming, exquisite sorrow of this book.

Mood is relatively clear in Scribe when so much else is hazy (names, loyalties, pasts, futures). Also uncertain is the quotient of supernatural occurrences. A boy the narrator encounters in the woods may not be real, or perhaps the narrator herself is not, at least at the time of the encounter; another boy plays a trumpet with a voice of its own; a poisoned meal kills a person too slowly to be anything but witchcraft. All of this makes the cruelty of Billy Kingery even more vile, the dialogue even starker.

The prose slides in and out of the lyric register as smoothly as a skate blade on ice. “I have been made fat from the labors of others,” reads the pivotal document of the novel, the letter the narrator writes for Hendricks, “from the kindnesses and charities of those who meant me no harm. I have often meant harm. I am carved from the rock of it.” When asked to deliver Hendricks’s letter, and thus to leave her house, the narrator muses beautifully on the haven where she lives:

She sensed it again, hanging in the smoke-spumed corners of her witch’s kitchen, deepening along the pine planks of her floor. Pure, pooling desolation. For years she had vowed to stay here, whether they came to burn her or bury her or lift her onto some kind of imposter’s bier… It wasn’t her fate to minister to the open world as her sister had done. She had inscribed another destiny—to be the unsouled one, the rememberer. She could not leave this place.

The risk with an ephemeral novel like this one, with an unnamed narrator and an unspecified universe, is a reader’s inability to stay involved with the text. An author must be especially skilled to maintain interest in abstractions rather than concrete details. But Scribe is so beautifully written that it sweeps the reader in and buoys her for its entire, brief page count. And Hagy has an exacting sense of what a reader needs in order to hold on through vague circumstances. Objects keep the reader company: hatchets, stones, paper. The voice of the narrator (determined, but not entirely honest) fills the reader’s ear. The menace of men who want more tenses her jaw.

Scribe calls to mind another short, potent book, Gaétan Soucy’s The Little Girl Who Was Too Fond of Matches, although the language of Scribe is less bold and the depravity of the characters takes different shapes. But Matches, too, is about a group of connected people in isolated circumstances, about dead family members and strange magic. Both books have horror at their hearts, but Scribe is a gentler, more grieving horror. Men exhibit ordinary corruption in Scribe, while Soucy’s book deals with aberrations. Additionally, Soucy’s book feels like a Cronenberg film, leveraging body horror and human cruelty, while Scribe feels more like a folktale—like a story passed from hand to hand across time, peopled with characters more myth and amalgam than flesh.

Scribe has no lessons, though, nothing to put in one’s pocket and feel better about. It also has minimal oral qualities, and even comments on itself as a written document:

“I used to write letters. Just the way people wanted.”

“They didn’t write them on their own? To save theirselves time?”

“They didn’t,” she said. “They don’t. It’s not really about saving time. It’s more about laying out the language of all you’ve done or failed to do, all you’ve said or failed to say, in front of another person. For a long time, I was that other person.”

“And what are you now?”

“Tired,” she said. “Finished. I feel very finished.”

Despite its diminutive length, Scribe is an unforgettable book. It’s a wash of beauty in language and ugliness in human nature. Redemption is a complicated problem in the novel rather than a clean ending, but the conclusion, sorrowful as it may be, offers a bit of hope. Whatever war the population of this novel is recovering from, better times may be ahead: through memory, and the power of the written word, kindness will remain.

*

Katharine Coldiron’s work has appeared in Ms., the Times Literary Supplement, the Kenyon Review, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. She lives in California and at kcoldiron.com and tweets @ferrifrigida.