by KATHARINE COLDIRON

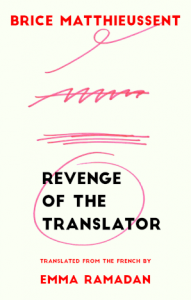

Brice Matthieussent, Revenge of the Translator, translated by Emma Ramadan (Deep Vellum, October 2018), pp. 352

I truly do not know where to begin with Revenge of the Translator. It’s a metatextual novel, and it’s confusing, sexy, intelligent, funny, disarming, irresistible. Normally I would save a string of adjectives like that for the end of the review, rather than putting it at the beginning, but this novel turns the act of writing upside down (figuratively and literally, on the landscape of the page), so I am doing the same.

Most of the pages of Revenge of the Translator place their text below a horizontal line, an area designated as the translator’s home space: the location of his work and the only area he possesses to reveal his existence. Many of the pages use an asterisk to refer between the translated novel’s body—above the line—and the translator’s home, but the asterisk is most often attached to blank space, because the translated novel does not actually exist. See, I’m already getting tangled up in attempting to describe this book. I can’t even explain the print layout, much less summarize the damn thing.

Okay, let’s try it this way. Have you read Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler? It restarts itself every chapter, tumbling its narrator through multiple unfinished narratives, making itself an inexplicable, unreproducible matryoshka doll. When I read that book, I felt twinned senses of utter joy and utter sorrow: joy that someone had written the book of all my readerly fantasies, the only book I ever wanted to read, and sorrow that there was only one book exactly like it. There are things about the book I don’t enjoy—the unshakable maleness of it, for one thing—but it’s still, genuinely, the singular and unrepeatable book of my dreams.

Or so I thought. Brice Matthieussent has written another one.

To be fair, this one doesn’t do exactly the same thing as If on a Winter’s Night. Revenge of the Translator’s metatext concerns itself primarily with translation rather than storytelling: the muzzy lines between translation and composition, the layers that exist between author, character, translator, reader, and author again. And while If on a Winter’s Night moves ever forward, this book circles repeatedly around small nodes of meaning: a crown of flowers, a bizarre painting of a puppet, Vladimir Nabokov, the translator’s asterisk repurposed conceptually and in physical objects, and “secret passage” as a multi-meaning concept.

I seem to be wandering away from clarity. I don’t know what miraculous human being wrote the summary paragraph on the back of the book, but it successfully untangles the three layers of books existing here. Those layers being: Revenge of the Translator, the book I am reviewing; Translator’s Revenge, the book being translated by Trad, one of the narrators of the book I am reviewing; and N.d.T., the book being written by Abel Prote and translated by David Grey, characters in the book Trad is translating. Prote and Grey tussle over Doris, a character so irresistible she might as well be Aphrodite (leading me to write in the margin “are all French novels about sexual jealousy?”), and then Trad transcends space and time to jump into the plot of Translator’s Revenge and meddle with the characters. Predictably, he, too, succumbs to Doris’s, um, “secret passage.”

I marked a few dozen pages in Revenge of the Translator, some of which I should probably quote here, but I can’t bring myself to do it. Quoting is, to me, one of the only true chores in critical work. I never really know if I’m giving a sense of the book to you, the reader of this review, or if I’m doing something closer to making a private joke between myself and the book. Which isn’t helpful to anyone. The book cannot enjoy my joke, as it is not sentient. Plus, figuring out how to hold the book open while I’m typing is irritating. Matthieussent’s prose is very fine, as if this were his tenth novel rather than his first, and he’s extremely funny and capable of writing in multiple registers. Do you really need quotes to prove that? I’d prefer that you trust me.

Other things I want to point out: Doris’s sexual monologues, which are a little like Molly Bloom’s famous soliloquy at the end of Ulysses, only very much more French. (If this is purple prose, paint me lavender and take me to bed.) The writerly usage of time, wherein time doesn’t pass in a way recognizable in real life, and why should it? (What writers can do on the page has nothing to do with what humans do in real life.) The way Woody screaming “YOU ARE A TOY” at Buzz Lightyear echoed in my head toward the end of the book, because I felt that Matthieussent was screaming YOU ARE IN A BOOK at his characters, and possibly at me.

Finally, I wish to acknowledge the mind-bending work translator Emma Ramadan has done to make this book exist in English. On any scale of book translation, from book-level to sentence level, what an impossible project! But she achieved it. I’ve interviewed her for Vol. 1 Brooklyn, because I was so impressed I absolutely had to know how she did it.

Have I convinced you to buy the book? That was the point of this review. Revenge of the Translator is one of a kind, one of the great metatextual novels of the 21st century (so far), and it’s difficult for me to be comfortable with a statement that bold, but honestly, it really is that good. If you enjoy the act of reading at all, get it, read it, teach it, savor it.