by JESSICA Q. STARK

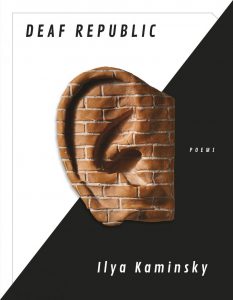

Ilya Kaminsky, Deaf Republic (Graywolf Press, 2019), pp. 96

An infamous and oft-misquoted line from the philosopher Theodor Adorno reads, “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” What is partially suggested here is that poetry, by way of making humanity’s deepest traumas palpable through language, risks reifying the very acts of violence about which it writes. Ilya Kaminsky’s long-awaited second poetry collection offers an alternative view. With Deaf Republic, he demonstrates that poetry, as a re-languaging and destructive force, is exceedingly necessary in facing our deepest flaws. The collection opens during a time of political unrest in the fictional territory of Vasenka, and unfolds episodically, following violent atrocities in a town under militarized occupation. A bruising, haunting examination of humanity’s paradoxical reserve for great compassion and endless cruelty, Deaf Republic holds an unsettling gaze on how we love amid chaos and despair. Kaminsky beckons readers to contemplate the contours of humanity’s untidy resistances to violence through the unexpected terrain of willful silence, a tender kiss, the untimely birth of a child, the haunt of a lover’s memory long after the finality of death.

The first poem of the collection, “We Lived Happily during the War,” provides an epigraph to the two-act, loose narrative structure of Deaf Republic. In accompaniment to the collection’s epilogue poem, “In a Time of Peace,” this poem situates us in the present moment, where the narrator describes “around my bed America / was falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house.” As introduction and conclusion, these poems complicate how we consider time and place during war and peace—the paradoxical standards that we hold for each category and how they collapse under the often-neglected violence of current neoliberal globalism. As much a parable of past human histories as it is a hard examination of the contemporary moment in a “peaceful country” like our own, Deaf Republic asks us to unlearn the conventional chronologies of violence to provide an intimate portrayal of the complexity of the human spirit’s methods of survival amid devastation.

Born in Odessa in 1977, Ilya Kaminsky and his family fled the anti-Semitism of post-Soviet Ukraine in 1993 and were granted asylum in the United States in 1993. Hard of hearing since a young age, Kaminsky brings a searing attention to the reverberations of trauma and the reformulating agency of silence in the wake of political and personal turmoil. This collection, which weaves illustrated hand signs beside text, takes hold of the conflicted place of silence and its interwoven connotations of complicity, fear, resistance, and shame. Deaf Republic asks “What makes silence? How many kinds of silence are there?” Incalculable, silence permeates Kaminsky’s collection as something radically errant in the cold calculation of a militarized occupation. From the poem, “While the Child Sleeps, Sonya Undresses:”

such is the silence

of a woman who speaks against silence, knowing

silence moves us to speak.

Kaminsky “knows silence” as a way of unknowing history’s long parade of violence, of re-encountering our capacity for compassion, and the effect of withholding description, sensation, and logic in addressing acts of unspeakable violence by human hands.

The two acts that compose the majority of Deaf Republic follow a handful of narratives about Vasenka’s inhabitants under militarized occupation. Act One begins with a brutal murder and its repercussions: the public shooting of a young deaf boy by a soldier and its gunshot that renders the town deaf. The townspeople’s deafness plays a resistant role against the cold calculation of the soldiers’ armed intrusion of Vasenka. Soon after the shooting and the onset of deafness, the soldiers fear those afflicted as potentially “contagious.” Kaminsky explains in his endnotes, “[i]n Vasenka, the townspeople invented their own sign language…as they tried to create a language not known to authorities… The deaf don’t believe in silence. Silence is the invention of the hearing.” In this way, Kaminsky’s resounding answer to history’s violence is no answer at all; the silence of the townspeople defies logical description. To hear, to explain, to account through language the contours of violence grants forms to unutterable trauma. Any attempt to explain what caused a violent act (a war among nations, a military occupation, an incidence of laughter) insufficiently justifies the act itself. Kaminsky weaves silence around reverberating moments of cruelty, not allowing them to settle with reason and easy forms of explanation. In “Alfonso Stands Answerable,” the omission of details mirrors Kaminsky’s attention to the radical agency of silence:

I run etcetera with my legs and my hands etcetera I run down Vasenka Street etcetera—

Whoever listens:

thank you for the feather on my tongue,

thank you for our arguments that ends, thank you for deafness,

Lord, such fire

from a match you never lit.

“Etcetera,” is a word that repeats throughout the collection—it describes an unspeakable reaction to unsettling reverberations. The speaker’s gratitude for deafness, parallel to the linguistic withholding in the repetition of “etcetera” in lieu of description, allows for inhabitants to occupy “a language not known to authorities,” to inhabit an exiled, exempt space from official language, the state, and its violence.

Act Two explores the clandestine resistance efforts of the townspeople, led in part by the dynamo owner of the town’s puppet theater, Momma Galya. The tragedy of this section interacts delicately with moments of lightness and humor. Galya’s brazen defiance, her iconic green bicycle, and her enchanting disregard for danger fuel the wild, roving forms from poem to poem in this section. In addition to nurturing puppeteers that systematically murder soldiers behind closed doors, Galya hides an orphaned baby whose parents were both killed by soldiers. She is, like the illustrated hand sign at the end of “Theater Nights,” the symbol for a struck match lighting up the town—a burning resistance despite the odds being so obviously stacked against her favor. From the poem, “When Momma Galya First Protested,”

In a time of war

she teaches us how to open the door

and walk

through

which is the true curriculum of schools.

Wrapped up in Galya’s fierce persona is the radical dissent of small, tender acts that permeate Kaminsky’s collection: the simple opening of a door, the washing the shoulders of a lover, the quiet holding of an orphaned child among soldiers. Galya’s presence cultivates the tenacity of living in excess of state boundaries and the seemingly inescapable reach of its sanctioned violence.

While acts of violence occupy the pages of Deaf Republic, a greater and subtler thread running through the collection focalizes tenderness, joy, laughter, and shared compassion among Vasenka’s inhabitants. Poems like Act One’s “Lullaby” present the baby Anushka, “little earth of six pounds,” as an errant, callow body learning to walk among the hard terrain of soldiers. Love and sex scenes between Alfonso and Sonya, as well, clash with the seemingly persistent interruption of death in the occupied town. Significantly, Kaminsky affords a quietude to these fragile strands. In “Before the War, We Made a Child,” Alfonso withholds details in recollecting moments of intimacy, exclaiming: “Sonya! / The things we did.” Unlike episodes of violence that are described in plain terms, these unexpectedly gentle moments elude exact detail. In this way, Kaminsky protects these scenes, houses and nurtures them—like the little baby Anushka—in silence. These poignant moments, unfolding beside horrific episodes of a town in disrepair, illustrate the persistent fugitivity of love in the wake of oppressive force.

The exposed nerve of human compassion flickers in reflection of an irrational, ungovernable spirit at the heart of Vasenka. Deaf Republic suggests that even in this seeming wasteland (of Vasenka or of our own present moment) there are silent, undeniable undercurrents—signs of life, of laughter, reverberations of human love—that move us beyond our collective barbarisms. Kaminsky’s work re-writes militarized territory with a lovelorn disobedient silence, in protest of casting violence as humanity’s historic totality. For in the space between history’s bombardments lies nothing, lies everything—love, touch, thought, life, breath, quietude—that are exceedingly necessary for our ongoing survival. “Silence, like the bullet that’s missed us, spins—”