by JESSICA Q. STARK

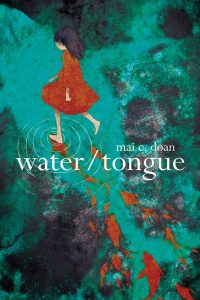

mai c. doan, Water / Tongue (Omnidawn, 2019), pp. 80

This review originally appeared in the Winter 2020 print issue of Carolina Quarterly.

Lifetimes ago, mai c. doan and I shared the same elementary, middle, and public high school in a suburb outside of Los Angeles and graduated in a class of 800 students. It seemed as though we didn’t share much in common beyond our schools during those slow years of limbs and concealment. In retrospect though, I had always felt a pang of connection to her then for at least one obvious reason. She was the only other half-Vietnamese girl in the whole big school that I knew, and the simple fact of our shared diasporic roots felt like clasping a tiny thread of neon against a mostly white backdrop. Back then, however, the energy I spent trying to blend in mostly muted that unique and unsayable connection.

After high school, she moved to San Francisco where, years later, I would also live. We met once for drinks in the Outer Sunset and late that night we awkwardly danced together in someone’s darkly-lit, carpeted living room surrounded by drunk boys. The encounter was simultaneously serendipitous and vague. We never met up again. “You dance like me,” was what I remember her saying. These experiential brushstrokes have nothing and everything to do with mai c. doan’s debut poetry book, Water / Tongue, which traverses what it means to be a tiny-feeling, mixed-race body among swaths of other bodies, big cities, untenable histories, their traumas. It’s about how to extract what’s no longer useful out of the whole mess of it in order to keep on living.

She begins Water / Tongue with an epigraph:

“The ordinary response to atrocities is to banish them from consciousness. Certain violations of the social compact are too terrible to utter aloud: this is the meaning of the word unspeakable. Too often secrecy prevails, and the story of the traumatic event surfaces not as a verbal narrative but as a symptom.”

While challenging secrecy, Water / Tongue honors silence. An undercurrent throughout the collection preserves a disorientation of distinguishable people, chronologies, and discrete memories. The first sections of the book follow a loose chronology of years accompanied by short, lyrical descriptions counterintuitively leading up to an “embryonic dream state.” Although sequential, there is no discernible order in the years skipped in her chronology. It’s as though doan crisscrosses generations as an active form of reorientation of (re)birth and shared memories, inviting the possibility for shaping a new, collective life-form—one that is “soaked in your terror” and full of rage against the silent implication of undefined, irrepressible trauma.

In the first part of the book, titled “Dust,” doan offers a question that acts as a pivotal hinge to the book and its political stakes: “the dead are more alive than the living and I want to know why.” In speaking to this interrogation, several poems in the book resemble acts of witness and witnessing. In an untitled piece, doan writes,

“i didn’t want to be left alone overnight in the hospital with X

i didn’t want to be left alone

i didn’t want to be left

in the hospital

the nurse changed the bedpan

i changed the bedpan”

The poem moves back and forth between the witness and witnessed in the first few stanzas, ending in repetition of an unidentified subject X under state control.

“X was under the care of the state

because

X was under the care of the state

because

the pills didn’t work.”

The effect confuses anonymized subject-positions of who is being acted upon in the scene. Memories traverse generations. As a result, the speaker explores non-linear forms of memory and highlights the afterlives of trauma enacted by the state. What remains in the dust and history of these “small” violations? Of their unarticulated experiences? How might these scars recur across generations? Repetition factors heavily throughout Water / Tongue—accumulations of repeated words take on incantatory magic as they are reiterated and redeployed under new contexts. In so doing, doan empowers “tiny” narratives that are typically overlooked by mainstream (white) culture: “tiny ashes. / tiny stars. / tiny dust settles / and sticks to tiny walls.” By repeating and folding the lyrical subject into these memories, doan demands attention to the small, singular body that is conventionally disempowered, anonymized, and silenced under state control. Simultaneously, she obscures a specific attention to the individualized body; her memory is at-once hers and the witnessed body occurring across a non-linear grasp of time.

Epigenetic trauma, the idea that trauma can leave a chemical trace on a person’s genes and then be passed down to later generations, is still contested territory among contemporary researchers. A 2015 study discovered that the children of Holocaust survivors had epigenetic changes to a gene linked to cortisol levels and related stress responses. While the study’s conclusions call for more expansive studies, the findings have incited new attention to the neglected ways that we potentially inherit familial and/or generational trauma. In “I.” doan writes:

“if i speak if i articulate this new American body into new American parts if i articulate if i name if i name myself using correct American words if i articulate this non-American suffering[…] i become an American narrative i become state-sponsored i become an American narrative”

Her streaming, unpunctuated language here evokes a hurried, grasping form of articulation of what it means to be, to speak, or to articulate against epigenetic trauma. In the following poem after “I,” doan repeats the paragraph, but omits all instances of the word “American.” From the perspective of being mixed-race, she calls into question how to define oneself outside of the limitations of nationality and its binaries that problematically shape identity and identification. These mirroring poems queer the lyrical subject as multiple and undefined, in stark resistance to the cold calculation of citizenship and being “defined” by the state. To articulate a narrative without the modification of “American” reclaims an unknown and murky space of identity—one that both troubles and recuperates what it means to be both American and politically non-complicit.

To “articulate” in this poem takes on multiple meanings. “Articulation” means both the act of giving utterance as well as a movable joint between rigid bones or parts of an animal. The complexity of doan’s craft recognizes the power of reshaping language and its undeniable relationship to the physical body. Trauma in this way manifests as physical symptoms in need of healing, and historical violence wields dire consequences for the body’s ability to thrive. Articulating these silent narratives provides a necessary release. Unpunctuating sentences and avoiding conventional titles for these poems, doan challenges the rigidity with which we define ourselves and our ancestors’ histories. Folded into ourselves is genealogy, nationalities, personal experiences. The run-on sentence here acts as ongoing, imaginative, connective tissue—a movable joint—between seemingly static histories that compose a single body. To put words to an unarticulated “feeling” in one’s body becomes a ceremonial extraction of colonial power to silence or keep still the colonial subject.

The final section of the collection, titled “Extractions,” provides an accumulation of large, oppressive structures that are, by language, ritually released. Things like “assimilation,” “clinging to the status quo,” a “lost tongue,” and “military masculinity,” are scattered across each page of this section. Like the final step in a spiritual cleansing, these ghosts are named and dismissed in the author’s final act of “QUIETING THE STORM”—a line that concludes the poem.

What I found most interesting in this ceremony that composes the book writ large is the tension the author holds between loudness or declaration, and an antithetically soft, femme space. doan nurtures (rather than eradicates) a pressure between sorting chaos (“the storm”) and acknowledging one’s fate, epigenetic trauma, and the unseen / unsayable that resides in one’s body and in one’s seemingly small place in history. This liminal position embraces a unique attention to feeling, healing, and living with your body’s ghosts. Not to simply dismiss oneself of them, but to acknowledge their presence, their pain, and to allow them quieting release.

One of the most obscured yet deeply seated ghosts in Water / Tongue involves Vietnam’s heavy history of colonialism. She writes:

BEFORE Chinese occupation brought Confucianism

BEFORE French colonialism brought cows

BEFORE U.S. empire brought capitalism

doan undoes history’s trudging chronology of Vietnam’s occupation here—in the world of Water / Tongue the Vietnamese diaspora might exist apart from the war in Vietnam, from French colonialism, even from ancient Chinese occupation. Looking at it on map, Vietnam exists like a tiny body of a country gently curving in on itself in the South China Sea. To know Vietnamese culture is also to know its history of occupation: cuisine staples reveal residual French tastes, and French was the “official” language of Vietnam from the mid-19th century until its declared independence in 1954. Water / Tongue seems to imagine (even if impossibly so) a Vietnam before colonial violence and its stains on Vietnamese culture. For me personally, I know I would not exist without the instance of my mother immigrating to the United States from Vietnam in 1975. Therefore, I simply would not be living without the occurrence of the American war in Vietnam. For me, doan’s work opens up new possibilities for living as an autonomous body unoccupied and undefined by a series of historical and violent circumstances. She provides a hidden stairwell out—guidelines for how to dwell within that conflicted space of the diaspora, and how language temporarily relieves us of its strain.

Water / Tongue is a brief book—almost too short. At the end, I wished for more expansion before its end. There were moments, as in an untitled poem that begins with “REMEMBER WHEN,” that I felt that doan was just getting started in writing how we find ourselves folded and permuted into large, structural systems beyond our control. Other moments suggested perhaps other under-explored, visual territories. There are two instances of photographs included in the book, which present shots of petals on the bottom of an emptied bathtub. These images were so fraught and evocative; I thought, why aren’t there more? Where are the others? A glimmer, then no more. But perhaps this is an important part of the design of doan’s magical, fleeting gestures. Serendipitous and vague. I meet doan’s gentle truth—like the flash of our encounters when we were so achingly young—briefly, brilliantly in the dark before the sun came up again, and we were gone.