by DEBORAH BACHARACH

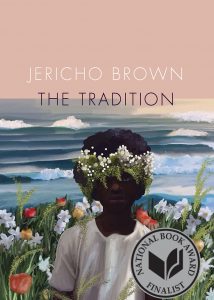

Jericho Brown, The Tradition (Copper Canyon Press, 2019), pp. 77

This review originally appeared in the Spring 2020 print issue of Carolina Quarterly.

I’ve designated this my personal year of the book review, but this is my first where I actually knew and loved the poet’s work before I sat down with the book. I’ve read Jericho Brown’s other two books, Please and The New Testament, heard him read recently, and a previous published poem from this book, The Tradition, (Duplex [I Begin with Love]) made my favorite poems of 2018 booklet that I gave as a family holiday gift. But squealing about the amazing turns, the clincher endings, the way he invented the duplex—an entirely new form—does not a review make. So, I’ll take a deep calming breath. Here’s what you must know. Jericho Brown is a Black, gay, Southern man and all those identities inform The Tradition. The traditions Brown takes on in this book are partially Greek mythology and Christianity, partially the legacies of slavery, Black power and gay love. He brings us these themes through the traditional craft of poetry and makes it anew.

One thing I’ve learned from writing so many book reviews is a great book of poetry should cohere—each poem exists in exactly the right place to make a unified whole. Brown makes this happen. In addition to linking poems that abut—for example, one poem ends with “home” and the next starts “In my front yard”—Brown braids throughout Greek myths, the naming of flowers, and desire. Brown’s authoritative voice that can say with a devastating calm “The way anger dwells in a man / Who studies the history of his nation” flows through the entirety of the collection.

Brown’s voice is almost conversational at times, like he’s telling a story to friends. He even comments on it himself—in a poem about what it means to be “Blk” entitled “After Avery R. Young,” he writes, “The blk mind / Is a continuous mind. I am not a narrative / Form, but dammit if I don’t tell a story.” Yes, he tells a good story, but the line breaks, turns, and endings add another layer of power. By combining and breaking sentences across the line, he squeezes in multiple meanings like when he writes of his mother in “Hero:”

“She cried at funerals, cried when she whipped me. She whipped me

Daily. I am most interested in people who declare gratitude

For their childhood beatings.”

Because of the line break after “gratitude,” Brown first makes us think he is yearning to be like the people who “declare gratitude.” Perhaps he wants to live on a higher plane than a life filled with resentment and anger, but the rest of the sentence flips that meaning, letting us hear “most interested” in an almost sarcastic tone— this speaker is no way grateful for daily beatings. The line break lets us hold both meanings and the complexities of these dark moments.

The titular poem “The Tradition” starts with a list of Latin flower names and puts the focus on black families working the land, knowing the flowers, and wanting to be in control of their world, their destiny. When the flowers become the young men men sped up too fast, I did not see the turn coming:

“Planted for proof we existed before

Too late, sped the video to see blossoms

Brought in seconds, colors you expect in poems

Where the world ends, everything cut down.

John Crawford. Eric Garner. Mike Brown.”

The names at the end, of young Black men recently killed by police, parallels the names of the flowers at the beginning, both completing the poem and opening it up like the tolling of a funeral bell.

The poem “As a Human Being” (as with so many others) is a master class in poetic turns, in dramatic changes in focus or feeling. The poem starts with a philosophical concept “There is the happiness you have / And the happiness you deserve.” This sets the reader up to consider why someone might or might not deserve happiness. Who is making the judgment? Brown then turns that musing into a simile for how the speaker and his mother sit apart on the couch. At this point, all we know is they are waiting for her ride to the hospital, so she can join her husband who has just been taken away by ambulance. We then get the big reveal that the mother has to go because the son stood up to the father “since you’ve done what / You’ve always wanted, you fought / Your father and won, marred him.” In a final turn, the speaker, realizing that his mother is leaving him to care for the father, understands himself as free. I kept finding myself both shocked to be in this new place and feeling the rightness of it. The last line clinches the poem and my heart when Brown writes, “Free now that nobody’s got to love you.”

But Brown is not just comfortable with received poetic tools. He has made his own form—the duplex. He includes five in the book, all called “Duplex.” A duplex is a series of couplets adding up to 14 lines (that magic sonnet number) where lines get repeated but rephrased as is done in blues music and then circle back to the first line. The repeating lines make me read the poem slowly, hunting for how the variations change the meaning and move the poem forward. “Duplex” in the center of the book explores love, relationship and mortality:

“I begin with love, hoping to end there.

I don’t want to leave a messy corpse.

I don’t want to leave a messy corpse

Full of medicines that turn in the sun.

Some of my medicines turn in the sun.

Some of us don’t need hell to be good.

Those who need least, need hell to be good.

What are the symptoms of your sickness?

Here is one symptom of my sickness:

Men who love me are men who miss me.

Men who leave me are men who miss me

In the dream where I am an island.

In the dream where I am an island,

I grow green with hope. I’d like to end there.”

In a blog entry on the Poetry Foundation website and in his readings, Brown discusses his creation of the duplex by combining the ghazal, blues poem, and sonnet as a way to include all his identities. He also talked about cutting up all his orphan lines in the syllable count he was looking for, laying them down all around the house and letting his gut find the connection between lines. Understanding the process helps me understand the mystery in this series. There’s dream imagery. There’s ambiguity like the first line. I don’t know if “I begin with love” means he was conceived in love or means that it is his starting point in life or this is his treatise on the meaning of life. I don’t care. It’s all good to me. I want to be with a person who says that.

I’ve realized recently that I tend to put in placeholder titles for my own poems. For a poem about men growing flowers, I might have called it “Men in the Garden,” but Brown calls this poem “The Tradition.” And suddenly this poem is not about just one day or a particular police killing but a history of Black men’s oppression, one that has been ritualized and codified. The title adds depth and breadth to this poem grounded in small details and real names. He makes this small poem so much bigger with the title. And by using this title for the book, Brown centers Black oppression as an American tradition as well as the “Thighs and Ass” and intimacies of love between two men. At the reading I attended, Brown said his first book helped him get a job, his second helped him get tenure. This book he wrote just for himself. In The Tradition, he claims himself.