by DEBORAH BACHARACH

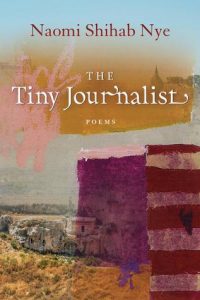

Naomi Shihab Nye, The Tiny Journalist (BOA Editions, 2019), pp. 114

Naomi Shihab Nye is a poet who has broken into the mainstream. Her poems of empathy like “Gate 4-A” and “Kindness” have gone viral showing up in Facebook feeds, personal blogs, and news articles. She has also published 30 books of poetry, essays, and stories and is the Poetry Foundation’s Young People’s Poet Laureate. Nye’s father was a Palestinian refugee, and Nye’s Palestinian identity has been a central part of her work. In The Tiny Journalist, a book of poems, cross-listed under Middle East studies, she takes on Janna’s voice. These poems are not dictation, translation, or paraphrase, but as Nye says in an author’s note, “the texts presented here are a blending of stories—my father’s, Janna’s, my ongoing research, and my own personal experience living there and on many subsequent journeys.” In this journey, Nye demands the reader pay attention to Gaza, understand life from a Palestinian perspective, and join her in witness.

There are a plurality of voices in these poems—Janna, Nye speaking to Janna, the poet speaking to the reader, even the moon has something to say: “Maybe it is wrong / that I am so calm” (“Moon over Gaza”). Because of Nye’s use of titles, person, diction, detail, and direct address, I had no trouble knowing who was talking and to whom. There’s a clear difference between Janna speaking to her social media followers in “Small People,” where Nye writes, “Janna says the camera is stronger than the gun” and Nye speaking to her readers saying, “I am mad about language / covering pain,” in“ISRAELIS LET BULLDOZERS GRIND TO HALT”, and if I ever considered being confused about who is saying “the saddest part? / We all could have had / twice as many friends,” the title, “Janna” keeps me on track.

It’s an irony of the modern era that the barrage of news from all corners of the world can actually make us less likely to pay attention to any particular crisis, especially an ongoing one like Gaza. These poems demand we pay attention. In “Gaza Is Not Far Away” Nye tells us:

The world’s largest open-air prison keeps ticking day to day—

alarm clocks, kindergartens, spinach mixed into eggs,

little blue backpacks for kids,

a few filter-water fountains, plastic bottles carried home,

and no, they can’t go swimming, can’t fish in their own sea,

can’t fly from their airport, can’t visit the so-called Holy City,

can’t do anything, basically, expect be human, be humane.

They can go to the Book Club and read books

And people far away won’t turn their heads to see

what Gaza is doing or how well they are doing it.

Or how hard it is.

Even when 500 people died from bombs they supplied.

By juxtaposing the concrete details that might also seem ordinary to an American—blue backpacks, book clubs—with daily deprivations an American can relate to like not being able to fly from your own airport, Nye makes Gaza real for her American audience. Then, she brings in the turn; it’s not some disconnected tragedy far away, but one abetted by American support. Many of these poems speak directly to the American relationship to Palestine, and Nye asks Americans to turn their heads back to Gaza not just because we all should pay attention to human pain but because we are culpable. Given how strongly she has had to ask us to pay attention, when Nye writes in “Unforgettable,” “Not easily will they forget / a place that let us all / sorrow this much,” I felt she is being wistfully hopeful, instead of certain.

Nye emphatically tells the reader that Palestinians are normal, human, people who could just as easily be them. So many times a speaker lets the reader know they didn’t go looking to be brave or have to cope with so much. As a speaker says to a tourist in “Regret”:

Excuse us this is not the life

we would have made or the way

we would have welcomed you

tear gas billowing over our streets

Regular

Usual

SOS

We are so tired.

In “Separation Wall,” a grandmother longs for the respite of a circus. At a reading I attended, Nye told us there was a cross border circus, one made up of both Israelis and Palestinians. The speaker in the poem wishes for a joyful normality that really could be. But even if they didn’t ask to be there, Nye tells us every resident in Gaza is called to be a witness. As she says of Janna: “It is her job to say / what she sees, what is happening.”

Nye asks the reader to focus on the poignancy and absurdity of a child having to speak out. And Nye herself, even in the diaspora, is a witness. In the poem titled “American Gives Israel Ten Million Dollars a Day,” she lists the price of the occupation: lawyers, artists, students detained and imprisoned. She tells us she too would not have chosen to keep watch for tanks “but this is my job.” (“Losing as Its Own Flower”)

Nye does not let the reader witness from afar by using questions to bring the reader in. At the reading I attended, I overheard one person in the audience say, “I never thought I’d like a poem called ‘Netanyahu.’” It would have been so easy to make this poem a rant. But, in “Netanyahu,” Nye does not lambast the long serving Israeli Prime Minister who is, as of this writing, trying to seize the West Bank and end Palestinian chances for statehood. Instead, she asks questions:

What does it mean when one person thinks

others deserve nothing?

What is that called?

If you know it is called, why keep

doing it?

Questions, coupled with the short lines, create a calm in the midst of this political storm. And these specific questions allow another way into the political quagmire: philosophical. What do we call it when we think one person deserves nothing? By asking the reader to supply the answers—dehumanization, slavery, hubris, colonialism perhaps—Nye asks the reader to become morally invested in the discussion. The problem is no longer about what that political leader is doing but what we let him do by not focusing on the moral bottom line.

Nye’s language is often very simple, not just because she is often channeling the voice of a child. In telling of what her father said about Jimmy Carter, she writes, “He saw us as human beings / He wasn’t afraid to say Apartheid which of course / it was and always had been.” This is straight forward story telling, no verbal gymnastics with polysyllabic internal rhymes, no oblique angles. Nye takes the misery and injustice of Palestinians straight on. That simple language makes her voice stark and honest. It reminds me of Ray Carver’s poetry where he sounds like your best friend telling you casually about the deepest emotions. As with him, the language does not let her hide her pain and her authentic connection and commitment to the subject.

Nye firmly situates Tiny Journalist in a political context, starting and ending the book with quotes about a desire for peace in the Holy Land, resilience of the people of Gaza, stark descriptions of apartheid, and a call to tell the story. At the reading I attended, fans of her poetry came, but also those who were also clearly declaring themselves activists for Palestine. She is reaching out to both those audiences as well as those whom she can teach. As she says in “You Are Your Own State Department,” “secret diplomats are what we must be.”