by BAILEY FERNANDEZ

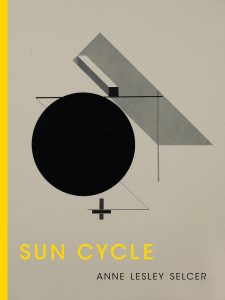

Anne Lesley Selcer, Sun Cycle (CSU Poetry, 2019), pp. 90.

This review originally appeared in the Summer 2020 print issue of Carolina Quarterly.

Anne Lesley Selcer’s most recent book of poetry, Sun Cycle, inhabits the center of the Venn diagram between poetry, critical theory, feminism, and aesthetics. While certainly poetic in both form and content — line, sibilance, and rhythmic language remain intact — the intellectual concerns weigh heavily on the book’s highly referential, hypertextual structure. It is an interesting, although not altogether faultless, read. After all, its entanglement within a school of theory which has reached a critical mass — essentially requiring academic training to understand — may compromise both the book’s status as poetry and its ability to engage effectively with social change.

Within the publishing ecosystem, Selcer emerges from inside a large crowd. Blank Sign Book, a collection of essays on aesthetics, was her first book-length publication. Readers will find its style and content evocative of Mary Ruefle (see, for example, Ruefle’s collection Madness, Rack, and Honey). With Sun Cycle, Selcer’s first book-length poetry publication, she begins to fully occupy the intellectual space — one both very erudite and very socially progressive — occupied authors on Wave Books such as Ruefle, Maggie Nelson, and Dorothea Lasky. An advertising blurb from Wave Books veteran CA Conrad confirms this suspicion. Curiously, it reads less like a recommendation and more like a personal letter: “Dear Anne Lesley Selcer …It is poets like you who make not being able to do it all alone okay,” they write. But, despite all of the connections to Wave Books, Selcer’s book is far from being purely derivative, and she has in fact created an impressively complex ecology of images and signs.

Throughout the day, the sun’s position in the sky casts the light that makes things visible, and it also renders the conditions for photography possible. Sun Cycle deals consistently with this motif. More philosophically, the sun’s relationship to the visible becomes the staging ground for the book’s primary philosophical theme: the concept of “form.”

In the opening poem, Selcer declares the appearance of “a hundred sunsets which refer to contemporary forms/to that which remain absolutely capable of forming a representation.” The sun generates (or, poetically speaking, “references”) forms, defined here in opposition to “representation.” For Selcer, the form is not fixed but is rather in a state of “becoming,” which can produce new relations. “Representation,” on the other hand, lacks generation, and reifies unpleasant social categories.

We may take note of two other examples. In the title poem, the sun seems to be a generator of form that is itself not form (“The sun’s a creep this week/Force transforms form at exceptional velocity”). Likewise, the first sentence of “A Treatise on Form” declares that “everything within the formal field becomes form. Form feels tactile to the formless, which is unseen, without name, unaccounted for numerically.” The “formal field” is analogous to the “force” of the previous passage, in which the transformation of form also is the “formal field” becoming form. Here, the light from the sun is primordial. It is prior to form, which exists in a settled state of identity only due to the sun’s influence.

Despite this “force,” Selcer also gives what is for her both a negative and masculinist side to the sun. The sun intones “I cannot cry” in the poem of the same title. In “Nouns by Bataille, Compiled for Elliot Rodger,” a poem consisting only of nouns connected by the verb “is,” she postulates an ontological equivalence between the words “form,” “body,” “man,” “eye,” “erection,” and others; while also including “her,” “parody,” and “indifference,” among others, in the same series of equivalences. The gesture of equivalence therefore hardly seems to be one at all. It is rather a messy series of ambiguities, one which permanently includes the aforementioned “sun.” This is not necessarily a weakness in the poem, but indicates that the operation of “form” through the creation of light is far from univocal in its meaning.

In fact, Selcer generated the form of the poem itself through a “formal field.” As she relates in the endnotes to the collection, “all words in part IV of the section “Sun Cycle,” “Nouns by Bataille, Compiled for Elliot Rodger,” are from the essay “L’anus solaire” by Georges Bataille. She continues by narrating the biography of Elliot Rodger — a mass shooter at the University of California, Santa Barbara that espoused deeply misogynistic ideas — but does not elaborate on the connection to Bataille. It is certainly not difficult to find aggressive masculinity in Bataille’s writing, and this position is clearly articulated by Maggie Nelson, one of Selcer’s likely influences, in her book The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning [1]. Selcer, however, does not draw the connection to Nelson. I will conclude here only that the generative power of the “sun” in its “formal field,” for Selcer, does create issues in its unified, “representational” forms.

The negative view of “representation” shows itself forth once more in the equivalence drawn between form and capitalism. In “Fronding and Intricate, ruined with colour,” the poem begins with the declaration: “if property creates meaning/a landlord is a baroque and overgenerative thing.” Is the landlord, for her, then placed in the generative position of the sun, the forces, the formless, and the “formal field?” The sun, in Selcer’s poetry, is once again subject to the ambiguous identities described in the “Nouns Compiled…” poem. For Selcer, it seems that the constant generation is multivariate, occurring on its largest level in the sun and individually in a variety of cases, both positive and negative, which produce the forms (or “forms of life”) which we inhabit.

Through these close readings, one might also get a sense of Selcer’s dense theoretical engagement. The back of the book contains a list of referenced texts. These include Oscar Wilde, Immanuel Kant, Arthur Schopenhauer, Jean Baudrillard, and Monique Wittig, among others, as well as the adult film actress Sasha Grey. Like “Nouns by Bataille, compiled for Eliot Rodger,” several poems are “found poems’ generated through erasure or other techniques performed on these existing texts. Unacknowledged by the author, I detected references to Gilles Deleuze (“lines of flight”), Jean-Luc Godard (“Goodbye language, or hello”), and others. The very conceit of the book — the equation of societal and aesthetic forms — may have root in Caroline Levine’s Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network.

Those unfamiliar with these texts, however, may find this book needlessly challenging and difficult. Not only are the texts not easy texts, but they are also never summarized, excavated, or explained at any point in the poetry. While I myself enjoy this poetry, I do wonder if the architecture of this book’s images may participate in elitist modes of production that connect both poetry and the dissemination of critical theory. Given this problem, many readers may decide that they want nothing to do with this book. Such a perspective is entirely understandable, and constitutes what may be a potential gap between elevated and progressive goals with the arcane, erudite, and highly combinative language used to express them.

Selcer’s book is a worthwhile read. It is not blameless, and occasionally its theoretical basis results in bad lines of poetry (“meaning is sex” in “The Picture of Sasha Grey,” even with the ironic tone of the poem’s last line, reads poorly). However, the book is at least intriguing theoretically, and I have taken away from it an interesting distinction between “form” and “formal field” which I find to be conceptually useful. In these small take-aways, one hopes that the book in-itself can become a “generative thing.”

[1] Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning, (W.W. Norton & Company: New York, 2011), 101. Nelson’s passage serves mainly to criticize Viennese Actionist artist Hermann Nitsch’s meat-and-blood-fueled performance art through Bataille’s influence on him. As an alternative, Nelson prefers the video art piece Family Tyranny by Tom McCarthy, which she believes exposes masculinist and sacrificial ideals rather than celebrating them.