by GEOVANI RAMÍREZ

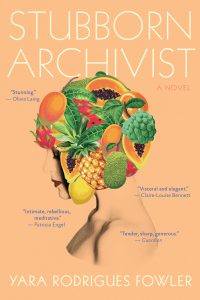

Yara Rodrigues Fowler, Stubborn Archivist (Mariner, 2019), pp. 400.

Yara Rodrigues Fowler’s Stubborn Archivist concludes with the unnamed half-English, half-Brazilian protagonist dancing on a beach in Brazil with her Brazilian friend Gabi as they listen to “tinny music” while behind them “the waves crush onto the sand.” Partly “tipsy,” the narrator drops her English inhibitions and bicultural misgivings about her authenticity by dancing in order to show Gabi that she is Brazilian as well as English, for while she does not “know the dance” that accompanies the music in the background, she does “know it a bit” and requires only the guidance of her Brazilian friend to help her recall the dance ingrained in her cultural memory:

“You do not verbalise the movements of your body. You concentrate on letting your body follow her body. Behind you the waves crush onto the sand.

Your body moves

(her body moves)

Your body moves —”

The irrelevance of words in this dance gestures toward the intricate ties between our cultures and our genetics, as if our bodies inherit the memory of motions and practices to which we have not necessarily been exposed. Following Gabi’s body motions and mimicking the oscillating waves, the protagonist recalls her Brazilianness. As importantly, here she rediscovers her womanhood and sexuality, something which she has only alluded to in rather problematic ways until this point in the novel. The motions of their moving bodies, paralleling the movement of the waves, are reminiscent of the relationship Kate Chopin draws between her protagonist Edna Pontellier and the sea’s allure in The Awakening (1899). One passage from Chopin’s novella is particularly helpful in illuminating the sensual qualities of the protagonist’s oceanside dance with Gabi in Stubborn Archivist: “The voice of the sea is seductive; never ceasing, whispering, clamoring, murmuring . . . The touch of the sea is sensuous, enfolding the body in its soft, close embrace.” In both works, proximity to the sea awakens women to the pleasures of their bodies and encourages the exploration of those sensations, but in Stubborn Archivist, it also urges the women to experience their own bodies through one another.

Traveling alongside the protagonist across Stubborn Archivist as she works through sexual trauma, depression, and physical illness, we rejoice at this reprieve from the protagonist’s perennial suffering. During this dance, the protagonist is at once comfortable in the natural elements of Brazil and with her body. The sound of the ocean adds to the rhythm of their dance and its crushing sound vocalizes the passion—for her Brazilian identity, for her body, for Gabi—the protagonist may feel at this moment. The ocean’s incessant and repetitive motion onto the land mirrors and sounds the performance of their interpolating bodies (“your body moves / (her body moves)),” joined in an intimate and quasi-sexual harmony that is at once gentle and pleasant, unlike the sex with her ex-boyfriend and sexual assailant which had “been good sometimes” but other times “ugly” (74). This dance offers the promise of new romance or at least the protagonist’s potential transition into a healthier view of her body. We can cross our fingers on the protagonist’s behalf, but we also know that the rest of the novel dampens the cheer of this moment. The dance is all the more beautiful because of the intense pain the protagonist has otherwise experienced in the novel. For, with the exception of this ending and a few fleeting moments, Stubborn Archivist is a somber text.

In her blog review, Reading Women Writers Worldwide, Sophie Baggot observes that Stubborn Archivist “is a beguiling insight into a Brazilian-English girl becoming a woman while treading a tightrope between multiple worlds.” Baggot here speaks in particular about the protagonist’s ongoing struggle to grasp and navigate her biculturalism, her half-Brazilian, half-English cultural identity as well as her Portuguese and English languages and her travels between England and Brazil. I would add, however, that the worlds the protagonist inhabits, and additional concerns central to the text, also include her life with physical and mental health issues.

Rodrigues Fowler tells B24/7’s Joe Melia that “my writing is a lot about sex, sexuality, bodies and sexual violence . . . To me it would be impossible to write about these things without also writing about colonialism, whiteness and how the imperial relationship between Europe and the Americas has shaped gender and sexuality as we experience it now.” In her debut novel, Rodrigues Fowler relates colonial legacies to contemporary European and Latin American (sexual) encounters. The story follows a young Brazilian-English woman who suffers from bouts of depression, paranoia, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and as the narrative unfolds, we see that her English ex-boyfriend Leo’s sexual assault of her has caused and/or exacerbated these conditions. The protagonist’s troubled history with Leo illuminates how sexism and colonialism, manifested through a European male fetishization of Latin American women, continue to overlap in the twenty-first century. At one point, Leo ruins a tender moment as they lay “both naked and in that effusing enthusiastic, revelatory mood” after sex by revealing to the protagonist, “I’d heard of you, half Brazilian . . . I had a thing for Brazilian girls . . . Used to love Brazilian Porn.” Brazilian women have been historically hypersexualized by Brazilians and foreigners alike, but Leo’s male gaze, to use Laura Mulvey’s term, goes further by equating Brazilian women generally with porn actresses in his sexual fantasies. By couching his initial interest in the protagonist within his fetish (“a thing”) for “Brazilian girls,” he reveals his dehumanizing lust for a particular type of racialized body, not in nurturing a romantic relationship.

Rodrigues Fowler challenges this objectification of Brazilian women in Stubborn Archivist by staging Leo’s denunciation and throughout the novel depicting the incessant mental and physical ailments the protagonist experiences from his sexual assault. In the scene I include below, Rodrigues Fowler carries out the former task and employs dramatic literary techniques that make Leo’s quasi public humiliation more pronounced. Though technically a novel, Stubborn Archivist—sometimes told through a third person narrator, first person protagonist narrator, or the narrator’s mother—looks and feels like a myriad of genres, modulating between a vignette, poem, play, diary, or conversation. In the passage that follows, Rodrigues Fowler writes from a third person narrator point of view, as if we were reading a novel, but visually we see that the words are formatted like a poem and, furthermore, the passage offers stage directions (e.g., “She fixes her eyes on him and then exhales,” “He covers his face,” and “She looks at him”) that dramatize the moment by insisting on the importance of performance in the text. Rodrigues Fowler transforms us into participants of this play and thus invites us to say these words aloud as we watch the scene unfold. It is a moment in which we are paradoxically assuming both the role of the protagonist and the perpetrator.

Rodrigues Fowlers’ hybridization of genres in particular reflects her decolonial aesthetics. In her interview with Melia, she declares, “I know that everything that I ever write will be about the Brazilian diaspora in the UK. I can’t see a world where I would make anything else (why should I?).” There is precedent for this genre mixing in the literary productions of non-Western women writers, including but not limited to those of Sandra Cisneros (whom Rodrigues Fowler quotes in an epigraph for the novel) and Ama Ata Aidoo. If we read Rodrigues Fowler’s postcolonial hybridized approach within this tradition of non-Western women writers, then we can appreciate the subversive quality of her form. Mixing genres in this way allows her to dismantle the conventions of the traditional novel, which has been the privileged genre and, as Lisa Lowe observes, the genre of privilege, accessible to writers whose socio-economic and political background has historically allowed them to write with more than other marginalized groups whose lack of privilege has historically necessitated their writings within other less preferred genres.

Her mixed approach to literary form also reflects Rodrigues Fowler’s insistence on verisimilitude. Genres, by way of their conventions and flairs, (re)shape knowledge and content. They can dramatize some aspects of existence, but obscure others in the process. Mixing genres, not just across the course of the novel but within particular passages such as the one that follows, allows Rodrigues Fowler to represent the multisensory experiences of life that account for the sounds and movements that shape our realities. In the following scene, she showcases her hybridized genre as she stages a confrontation between the protagonist and Leo:

“You remember at the end

I do

You remember at the end?

Yes

Some of the things we did, you know, how you were different, at the end—

He’s breathing quickly Yes. Yes

Her breathing is quick

She opens her mouth like shark jaws her lips part

I want you to know — she holds eye contact

She says his name aloud

She says his name aloud

She takes a breath—

I want you to know that they weren’t consensual

Fuck

He covers his face.

He speaks through his fingers—

She leans back.

He says — In the kitchen

She fixes her eyes on him and then exhales. Yes.

She looks at him. Then she says — But it was that whole time that — Winter.

She moves, as if to touch her phone in her pocket.

He reaches towards her in a panic and in a panic he says —

I loved you so much”

The above passage includes the only explicit reference in the novel to rape, and there is no indication anywhere else that anyone beyond the protagonist and Leo know about their violent sexual past. We do, however, learn that he has moved on with his life as she remains trapped by their shared history. The protagonist keeps track of him through Facebook, where she finds photos of “him by the sea,” “with some dog in a living room she didn’t recognise,” and in “a bedroom she didn’t recognise.” The images offer glimpses into his new adventures, and the new home reminds the protagonist that their past relationship has been replaced by the new life he has begun for himself. These changes, and especially the “photo of him wearing blue scrubs like on TV and smiling,” show that he continues to live a potentially satisfying and professional life despite his transgressions. The new photos bury his sordid past and along with them the memories of her traumas.

In fact, only moments prior to the scene above, Leo shows no contrition. When they greet, the narrator reveals that “He puts his arm around her body and shoulder in greeting, his nose in the damp hair behind her ear that still smells of shampoo.” He continues to make sexually suggestive gestures that allude to past intimate experiences and his ongoing fetishization of her body. The protagonist, on the other hand, continues to be physically and emotionally debilitated by the memory of his assault and finds herself often suffering in confined spaces alone. Rodrigues Fowler stages this dramatic confrontation at a bar to offer the protagonist an ostensibly safe public space, with witnesses around, in which the protagonist might make Leo accountable for his transgressions. The confrontation creates a reversal of power: As “She opens her mouth like shark jaws” to remind him of his transgression, “holds eye contact” with him (or “fixes her eyes on him”), and “leans back,” he finds himself “breathing quickly” and covering his face during the grand revelation.

What is more, the protagonist recasts their sexual relationship in a new light, one that rejects his obsession with exoticizing the Brazilian protagonist and replacing it with a narrative that accounts for his sexual assault on her. He loses his power to silence or overwhelm her, to encroach upon her body with impunity. In the exchange, he becomes tentative in his responses, finding safety in responding with few words. His answers to the narrator’s succession of questions are “I do . . . Yes . . . Yes. Yes . . . Fuck . . . In the kitchen.” Within this moment, the combination of words, which echo marriage (“I do”), sexual pleasures (“Yes . . . Yes. Yes”), and his fantasies (“Fuck . . . In the kitchen”) offer a rereading of their disintegrated relationship and sexual past. They retell their love story and sex life from the protagonist’s perspective, one that highlights the pain he caused her during sex and which conjures up those sex scenes to help him see that his pleasures were her pain.

Though by the novel’s conclusion the narrator does not share her experience with sexual violence with anyone, she nevertheless gestures toward either publicly denouncing him or reporting him to authorities when “She moves, as if to touch her phone in her pocket.” The description of her action suggests a premeditated plan to elicit from him, if not the response he gives, at the very least guilt and fear over his sexual violence. By reaching for her phone, the narrator places her experience alongside a transnational and transhistorical continuum of male sexual abuses of women, and her response to such assaults places her alongside other women across the world within the Me Too movement. The phone allows her to contact police officials to report his crime and/or to post his assault via social media for the world to see, and his panicked actions and words offer a comical, if repellant, conclusion to the spectacle. His uncritical and desperate attempt to dissuade her from denouncing him publicly on the basis that he “loved” her “so much” is a statement as hollow as his reasons for pursuing the narrator. He is afraid in this moment, not in love, just as when earlier he says “Fuck” and “covers his face,” he says so out of fear of the trouble this news could bring him, not because he is thinking about the indelible harm he has caused the narrator.

Although the novel concludes with the possibility for the protagonist to heal and regain confidence in herself as an authentic Brazilian and whole woman, she nevertheless suffers the remnants of her sexual trauma in the novel prior to and after her triumph over Leo. Rodrigues Fowler wishes as much to underscore the other parts of the journey toward healing that are less empowering, and she depicts this journey as one marked by ups and downs. Rodrigues Fowler also uses the narrator’s assaulted body in particular to represent the traumas of sexual violence that have defined the narrator’s existence. For instance, the narrator “had always thought she’d have grown into a grown up body by now — bigger breasted and tall” but instead remains as she might have been years ago when she began dating Leo at the tender age of “sixteen, fifteen,” physically as well as emotionally and psychologically stunted years after the incident. The assault informs her self-worth: Commenting on her feet, calves, thighs, belly, back, arms, hands, and elbows, the narrator observes disdainfully “look at this broken body / look at this broken up body.” She sees herself and body, not as it is but as she feels she has been left after Leo’s transgression. The sexual assault also exacerbates the narrator’s Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Rodrigues Fowler ties the narrator’s IBS to the sexual trauma when the protagonist’s anxieties over encountering him in the streets (prior to their confrontation described above) causes her body to attack itself. The narrator notes, “she didn’t tell anyone about it but she had heard a voice call her name . . . She ran home and sat on the toilet, shitting, sweating, her face in her hands.” After the encounter, we learn that “Overall, it [IBS] was getting better — this year the urgent need to shit only occasionally forced her out of bed in the morning. For this she was grateful” (245). Perhaps the encounter was necessary and has helped the protagonist recover to some degree from her sexual assault, but there is much more work to be done, and the experience of coping with these things is, as Rodrigues Fowler says in an interview with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, “often mundane, silly, hilarious, extremely lonely, intensely private.”

By discussing the protagonist’s IBS issues, Rodrigues Fowler resists the hypersexualization of Brazilian women and removes the protagonist’s body from the tray of consumption. Rodrigues Fowler expresses her desire to, through the narrator, “draw out . . . the disconnect between the sexy Brazilian woman and the Brazilian woman with IBS.” She replaces images of scantily dressed Brazilians on beaches and at carnivals with one of the narrator spending an “afternoon all curled on the cold floor of the big organisation toilets.” Rodrigues Fowler points away from the anatomical parts of the protagonist’s body that can be easily gawked at and consumed and instead toward the digestive functions that impact her life significantly and which at times incapacitate her, as in this moment. The protagonist’s body, then, is not merely an object of desire that can be enjoyed for sexual pleasures but rather a system of flesh and blood and fluids and organs and feces that allow the protagonist to exist but that she must also contend with at times in rather painful ways. The length of time (an afternoon) she is incapacitated for highlights both the accumulation of hours she has clocked coping with IBS over the years as well as how central it has been to her life, how much time in a day she must dedicate toward suffering through, managing, preventing, and/or coping with her disease. She has to, for instance, “avoid tight-waisted skirts” and “melted cheese” sandwiches as well as “Undo her button after lunch.” Yet, by contemplating the contradictions between the “sexy Brazilian woman” and the “Brazilian woman with IBS,” Rodrigues Fowler paradoxically opens a space for incorporating physical ailments into conversations of sex. IBS and other ailments, she shows us, are not distinct or antithetical to sexiness.

Rodrigues Fowler’s story is compelling, not only because of her ability to tell an interesting tale, but because of the techniques she uses in her writing to approximate life as it is lived and processed. Her choice to exclude quotation marks from denoting dialogue throughout the novel helps us see that quotation marks sometimes fail to accurately represent the (mis)communications in our disorderly lives. In the passage below, she employs a parenthesis instead of quotations in order to demarcate the gaps between what is said and what is heard or acknowledged. In the following moment, for instance, the protagonist’s dad desperately runs through a checklist of things (“did you lock the back door, who has the key . . .”) before departing, but he may very well be doing little more than talking to himself:

“They piled into the car (did you lock the back door, who has the key, okay one last passport check) with unclosed prepacked suitcases waiting for the traffic to thin through Wandsworth and Fulham and on that bit of motorway before Heathrow. Her dad, who was always sure that this year would be the year they missed their expensive flights, became more nervous like — Shit shit where did all this traffic come from? What time is it? What time is it? Bugger.”

As in the above passage, Rodrigues Fowler at times also combines different points of view within the same passage to account for the simultaneity of thoughts, conversations, and actions.

The changing points of view create the chaos and sense of urgency the family is experiencing as they attempt to account for all they need for their travels while in a time crunch. The alternating perspectives paired with Rodrigues Fowler’s omission of quotations, which might otherwise distinguish the actions from the dialogue, reflects the web of experiences, actions, sounds, movements, thoughts, and conversations that actually inform our daily existence. Life does not, after all, pause for us to hear a distinct line of dialogue, but rather it keeps going—we keep moving as we talk and (maybe mis-)hear.

As her title suggests, furthermore, a “stubborn” repetition defines Rodrigues Fowler’s novel and the protagonist’s ongoing archival memory project of reliving past traumas and recalling her family as well as personal history, and Stubborn Archivist is replete with repetitive, poetic moments such as the following:

“There was always here and there was always there.”

“Home is where the

Home is where the

Home is where”

The repetition is reminiscent of Gertrude Stein’s poetry (e.g., “If I told him would he like it. Would he like it if / I told him” or “Now / Not now/ And now. Now” or “Presently / As presently. / As as presently”), wherein the repetition of the same words begin to transform their meaning. In Rodrigues Fowler’s use of repetition, the restatements chip at the words to carve out different meanings, and they reflect the power of sound to alter the written word. As importantly, she employs repetition as an exercise to uncover/discover/recover the protagonist’s bicultural roots. The recurring, morphing lines create a haunting echo of the protagonist’s past but also gestures toward the future. Home for the protagonist remains both elusive and possible as she navigates her bicultural identity. It is both England and Brazil (both “There” and “here,” familiar and strange, comforting and alienating), and it also lies in both the English and Portuguese languages. She finds it in the fruits she eats at home and buys at a supermarket. The protagonist literally contemplates the fruits of her life in the following passage:

“amora

ameixa

amora

amoras were they blackberries or mulberries or

amora

namora

enamour”

“Only when she was older did she realise all that time some of these fruits had been living double named double lives one soft and wet and café de manhã

the other shrivel sour and in Sainbury’s.”

This recycling of words allows the protagonist to fuse her two cultures through sound, and memory—in this case, the memory of consuming and naming these fruits, of defining them by her relationship to their acquisition, manifestation, and rituals for consumption.

Various reviewers have already established that the Stubborn Archivist traces the bicultural experiences and transnational travels of the Brazilian-British protagonist and her family. One reviewer from Elle (UK) Magazine writes that the novel “beautifully explores the notion of home, belonging and trauma for people who, like this Brazilian-English writer, find themselves growing up between languages and cultures and identities.” This statement is quite accurate in noting the importance of the Brazilian diaspora in Rodrigues Fowler’s work, but I hope this review has also shown that Stubborn Archivist is much more than that, and I believe readers interested in trauma studies, women and gender studies, postcolonialism, and disability studies would benefit from experiencing this book. Rodrigues Fowler offers us a wounded protagonist whose life consists of tending to her wounds, and she leaves us with a dance that moves us back and forth between England and Brazil, colonialism and postcolonialism, girlhood and womanhood, and trauma and healing. We can only hope that, through future literary contributions, she will keep sharing with us that dance.