by JULIA EDWARDS

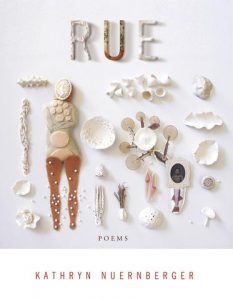

Kathryn Nuernberger, Rue (BOA Editions, 2020), pp. 104.

In an online reading series via Green Mountains Review, Kathryn Nuernberger declares that the closing poem in her new book Rue, “The Real Thing,” is “the closest thing a cynical, cranky person like me can do to get towards writing a love poem.”

Prone to cynicism myself, I would respectfully disagree with the implication that this collection is without romance. Nuernberger’s feminist speaker, though subversive and, indeed, cranky, is also one preoccupied with love. She lusts after “a guy with a really nice bald head,” writes an ode to cross-dressing farmers, and adoringly imagines her sixteen-year-old self with her lover at prom, having “kissed you all night long and then / written a very silly song about it.” She is in love with Carl Linnaeus, inventor of the book that first attempted to classify all living things, begging for readers to share in her passion: “I need you to love him too.”

Rue’s name comes from common rue, a plant used for birth control as early as Medieval times. Women would eat its bitter leaves in salads and drink its oils in their tea as emergency contraception or to induce abortion. With this eco-feminist framing at the forefront, Nuernberger’s book does not conjure up conventional love poems with happy endings or fill its pages with sonnets or aubades. But it does include poems that are intimate and honest about desire in all its sprawling and strange forms, as the speaker navigates the exhilaration and potential futility inherent in expressing it.

The author of works both archival and personal (most recently, a semi-personal collection of non-fiction essays, The Witch of Eye, and winner of the 2015 James Laughlin poetry award, The End of Pink), Nuernberger is a sharp witness to collisions between the natural and artificial world. In an ostensibly scientific poem, “The New Elements,” the speaker sits at a bar watching “people falling in love” while ruminating on her subjects: “the new ones exist / for only fractions of a second before / dissolving into more familiar atomic particles.” She understands that nothing new can last nor can the natural order of things be disputed, but still, she lets her idealism run away with her, ending the poem with: “Is it true that I’m hoping a stranger / might take me home? Of course it is.”

Nuernberger is keenly aware of her position as a woman moving toward middle age alongside a history of political oppression and social subordination to men. She challenges the masculine and the conventional with a practiced eye, fiercely, and in her words, with “radical honesty.” Her poems do not spare us any uncomfortable details –– groping male OBGYN doctors pulling the speaker’s baby out with a “huge suction cup,” the “lube-soaked, condom-covered dildo” that projects the sonogram of her dead baby, and the face of the dying “without dentures or muscles.” Instead of using pretty language to elevate or hide pain, Nuernberger leans into the indignities of being in a body, highlighting the unique precarity of women as bearers of life. This approach serves as a reminder of beauty’s proximity to ugliness and the deeper threats lurking below the surface of the procedural or mundane.

Admirably, she does not adhere to the trends of the day –– none of her poems are written in neat lyric couplets. Most of the poems in Rue are in free-verse, moving in deceptively deft stream-of-consciousness monostrophes down the page. This seems to be a deliberate rejection of the restraints that come with more traditional poetic forms and an interest in stretching a thought to its limits, diverging from an expected or prescribed pattern.

The opening sentence of “A Difficult Woman” spans thirteen lines, beginning with “I left the metaphor of myself I like best / in the rabbit warren and went to the office.” From the title, we are expecting a common stereotype to play out, but we are instead given something that is much harder to conceptualize: “the metaphor of myself” and its opposite.

The remainder of the sentence brings us away from metaphor, not into a situation that is more concrete, but into a hypothetical workplace that becomes more and more abstract. The sentence begins detailing and ranking the different levels of “professionalism” the speaker must abide by until finally, at the end of the poem, we come back to the metaphor of the rabbit warren: “Every little box is a warren and I try to stay inside, / but my haunches are itching springs and I want / to fuck over everything.”

But as soon as the speaker abandons the stuffy language of the office in pursuit of more carnal desires, we are faced with yet another simile: “like it is May/ and the Oak trees have just uncurled.” Nuernberger makes us aware that language is a slippery bridge we must cross to move from meaningless categories into the natural world. The question that remains: can anything be truly natural or organic with formulaic language as its necessary mediator?

We see this dilemma playing out in a number of places in the collection, such as when the speaker sees a crow stuck in a chicken wire at the Dollar General parking lot and compares it to her baby being cut out of her. The shock of this comparison is mediated by self-awareness: “Mercifully, the metaphors we have to live through / are fewer than the ones we think of.” In this instance, she celebrates the wild possibilities of imagination even while recognizing that our fantasies can become trapdoors leading to pain and fear.

Nuernberger’s speaker is skeptical of rhetoric, language, and even poetry. In “The Petty Politics of the Thing,” we begin in an office with a speaker who is “surprised by the teeth and meat-breath / of myself.” She mentions a “fight” that goes undetected under the surface of the “blue computer screens” and passive aggressive employee comments: “It was not the kind of fight / a poem can understand, so I’ll tell instead / about the cat who drug the newborn rabbit / from the nest under my porch.” Instead of using the cat and rabbit as a metaphor for the tension building beneath the surface of human pleasantries, she makes the animals the central, real event of the poem. Despite the speaker’s surprise at her animal qualities in the beginning of the poem, she listens to the wild rabbit inside her, who whispers, “I will fuck you up.” The speaker responds:

Oh, I love her. I love her

for how real she is. She can see through

even the most tangled bramble of rhetoric.

We are not animals, you learn over and over

in school, which is where they break you to

the florescent lights and geometry of so much

empty furniture in a room.

The poem breaks the barriers between the human and animal worlds by injecting an office setting rampant with cliched language with the raw brutality of animal nature. It is a moment where Nuernberger’s speaker, though human, bows to the power of the wild and instinctual – a quality that rhetoric fails to contain with its artificial lights and calculated speech.

It would be wrong to overlook Nuernberger’s humor. The characters in the office react to the “hypothetical” animal violence in comical ways. A veteran says, “You think that’s gruesome,” and everyone politely ignores him. This not only highlights the dismissal of the atrocities of war, but also the ways that our shared language fails to connect us in human experience; how violence has no place in common rhetoric despite its prevalence. We see the world through a mind both brilliantly engaged and spiritually distraught, seeking answers through the same rhetoric from which it wants to escape.

These concerns come through clearly in “Queen of Barren, Queen of Mean, Queen of Laced with Ire,” a poem about Queen Anne’s Lace as a birth control method and the lack of nuance in historical accounts of the lives and legacies of women. The speaker ends this account with a list of ires: “My ire at my terms. / My ire at my impossible wanting.”

Nuernberger ceaselessly questions hard truth and facts in relation to the world at large, history, community, her family, and herself. Of course, the question of what is true is topical in the face of an ever increasingly divided country with opposing senses of what is “real” versus “fake” news. Armed with evidence both anecdotal and textual, Nurenberger makes a case for these discrepancies of information spanning a much longer and wider timeframe.

In a number of the poems, such as “You Get What You Get and Don’t Throw A Fit,” Nuernberger brings this contemporary divide to a past context, guiding readers towards reorientation of the way we see history’s construction and the hierarchies of our world. For instance, she references Adriaen Coenen, a fishmonger from 16th century Denmark’s map:

Here’s a star that blooms its six spiny legs

right out of the abyss of its own mouth. If you are generous,

you might call it a jellyfish. If you are generous, you can

almost make his illustrations match up to the world as you

know it.

Though this cartographer took pains to document his natural world in an 800 page book, Nuernberger seems to be asking us to consider a more subjective view of history: “If you are generous” gives us the option to decide whether we want to see the drawing of the jellyfish’s anatomy as fact. We are also asked to consider whether “the world as you know it” is the same world we see in textbooks or whether someone sitting next to you sees it, too.

She ends the poem by noting: “Adriaen left out the mermaids, as you must, if you wish / for your enterprise to be taken seriously as scholarship / and nonfiction.” Then she speaks to the mermaids, “That we might / star every city on this page with the lives we have known.”

She seems to raise not only the point that women have been left out of the narrative, but also that there are mystical, feminine experiences that can’t be accounted for through linear storytelling, mapping out a chart, or scholarly work.

Facts and truth take interpersonal, domestic forms as well in this collection. In “I Want to Learn How,” the speaker painstakingly details an incident where a man in her town puts “his hand across [her] shoulder” regularly in a coffee shop. She presents a series of definitions of “nice” and “mean,” ultimately discovering that there is no outcome in which her discomfort will be truly understood nor will she avert the situation without suffering social consequences.

Rarer in this collection are the moments of beauty and untethered imagination, but when they do appear, they are striking, as in “Whale-Mouse”: “Moments when some extraordinary / person reaches across the grass / that separates you to hook just one / of his fingers around just one of yours.”

Nuernberger inquires about love not in the theoretical way she probes history, gender, or medicine. Rather, her exploration of love is a central, grounding force in this collection, giving it heart and saving it from becoming too moralizing. This speaker, though deeply critical of the structures and behaviors of those around her (particularly of men), does not paint herself as blameless.

As a reader, I begin to resonate with Nuernberger’s voice in the fifth poem of the collection, “I’ll Show Me Mine If You Show Me Yours.” This is where we see the collection’s central concerns begin to synthesize in a way that feels down to earth and universal: the burdens of motherhood, flawed history texts and literature, and intellectualism versus art and nature.

The speaker opens with the admission that she’s been eyeing a man in the coffee shop “like a woman who had been reading Rumi and also a tome / on the history of bear cults in Europe.” By letting readers know she can make fun of herself, she invites us to witness some of her personal fears about menopause, womanhood, and desire.

In this state of mind, she offers her critique of poetry: “Poets I admire have been known to say, / ‘First thought, best thought.’ But if that worked I wouldn’t / need to write at all. If that worked, I could just talk to people.” Then, after an existential series of questions about how difficult it is to know one another and the allure of “a maiden / in the forest who couldn’t keep her hands off the ears / of some enchanted donkey,” she answers her own question: “Because I don’t know / how to talk to people, I guess. Because I’m lonely.”

Here, she surprises us with the necessity of art and poetry as a medium for human connection. Only by questioning a more instantaneous production of poetry (writing down the first thought and trusting it) can we see the range of poetry’s capabilities. It is in these more vulnerable moments that we can expand with the speaker into a realm of fantasy and passion that may not be easily found in ordinary life. We can recognize the flaws and limits of our language, the racism and sexism of our past and future, while still seeking truth, love, and an appreciation for our natural world.

Perhaps the most convincing reason to read Rue is that Nuernberger does not lead us on with answers. She inspires us to keep asking questions, and to do so through whatever language you can find traces of love and hope in, which in this case, is poetry.

Julia Edwards is a poet from New York. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in POETRY Magazine, Bat City Review, Diode, and others. She holds an MFA in poetry from the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, where she served as poetry editor for The Greensboro Review. She is currently at work on a debut collection of poetry.