by SARAH LOFSTROM

Katharine Coldiron, Ceremonials (Kernpunkt Press, 2020), pp. 134.

A novella inspired by the 2011 Florence + the Machine album of the same name, Ceremonials is an ethereal dreamscape of a text. It embodies sensuous transformation in its rich imagery and in the emotionally-saturated relationships between characters. Katharine Coldiron’s work has appeared in Ms., The Washington Post, LARB, The Times Literary Supplement, The Guardian, BUST, The Kenyon Review, The Rumpus, VIDA, Brevity, and elsewhere. An editor and self described “dissertation doula,” Coldiron has produced numerous essays, book reviews, and fictional works. Ceremonials, published in 2020, is her second published book. The work of fiction details the story of Amelia and Corisande, who fall in love while at their boarding school. Corisande dies on the eve of graduation, and Amelia remains haunted by her absence. The novella explores the addictive nature of obsession, delicious youthful sexuality, and the tenuous veil between life and death. The novella’s unique strengths are found in its epicurean language, nuanced exploration of all that liminality can hold, and beautifully rendered ekphrastic resonances with the album that inspired it.

Told in twelve parts which oscillate between Amelia’s and Corisande’s perspectives, Ceremonials’ narrative arc dips between the past and the present, revisiting the flowering of Amelia and Corisande’s romantic relationship, Corisande’s drowning (Florence + the Machine fans will recognize the overt calls to “What the Water Gave Me,”) and Amelia’s fraught grieving process. The night that Corisande drowns, she writes

I went beneath. I found the lake bottom and I dragged my fingers through the muck, gathering pebbles and stones and shells, and I filled my woolen pockets with them. I hovered. My arms rose. The canoe floated, a seed pod, slightly darker than all else around it. I could not see the moon. It is entirely different here, underneath. Quiet, sweet. I know that Amelia came in after me. She found me by my hair, snagged it on her reaching fingers. Her arms proved stronger than the stones in my pockets. I know that they took me away from her by force. That they laid me out on the grass and covered me with a gray blanket and had to drag her off shrieking. I know that they buried me under the great oak tree and that my aunt came to see me laid in the ground. The Directress gave most of my things to Amelia before my aunt arrived. I know that the water was very cold. Until, eventually, I was colder. (29-30)

The passage encompasses the nearly tangible sensuality of the novella, replete with sensory descriptions that seem at once to echo and transcend the difficult, traumatic nature of the content discussed. Sight, sound, touch are all involved in this death. Rather than being sensuously devoid of perception, this death is rich in feeling and intimately crosses the boundary between life and death; the language thus mirrors Corisande herself, who is presumably passed and yet is retelling this scene in memory.

The novella is punctuated with sumptuous desire that feels at once distinctly earthly and necessarily out-of-this-world. Narratives of possession, identity, and self-making in the wake of love and loss are troubled and challenged, for Coldiron asks the reader to grapple with the physical and emotional divisions, or lack thereof, between Amelia and Corisande. The initial lines of the first section proclaim “You are not my Corisande.” But a few lines later, the text asks, “are you my Corisande?” echoing the constant collapse of singular selfhood and possession in love. Throughout the work, Amelia is grappling with her physical and relational orientation to her own self in the wake of losing Corisande, a struggle that is marked by continual slippages between the real and the unreal. One morning Amelia wakes in her bed to find Corisande there, accusing her of unfaithfulness. Amelia says

She says it or I make her say it and I don’t know which it is. I don’t know what lies in my bed tonight, where it sits on the spectrum between what I invent and what I perceive, but she turns over and I see her bright blue eyes, beacons in a storm of bedsheets, and she is as real there as she was when I dragged her out of the water six years ago. (65)

Coldiron does remarkable work in rendering both Amelia and Corisande utterly human in their devout lush understanding of each other and the world around them, while also conveying an embodiment of ghostliness, of an ethereal beyond.

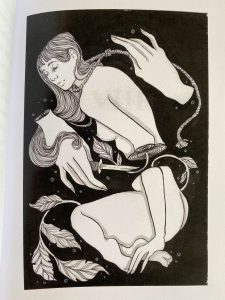

The novel is also interspersed with haunting and beautiful illustrations by Mariana Magaña de Lio which richly supplement the tone of fierce, aching tenderness. These illustrations speak both to the thematic content of the novella as well as the structural ekphrastic form—that the novella is a written fictional meditation on the album Ceremonials, and the visual art supplements this multi-genre exploration. The multitudinous form generously lends itself to reflecting on the role of liminality in genre-crossing as well as in the space between life and death, love and loss. Music, prose, and visual art unite in this work, asking us to consider the ways in which these unique artistic compositions all offer insights on themes of grief, sensuous beauty, and poignant love.

An omnipresent Corisande narrates the ninth section, observing her love from what seems to be a ghostly space of both life and death. She says that “Amelia’s path could be traced easily from where I laid. I lifted my hand and watched her travel the roads and lanes from wrist to thumb; she turned fingerward, and I followed her.” This eloquent synthesis of divisions between Amelia and Corisande’s physical bodies, as well as their inextricable link through what feels to be an unearthly transcendence of space and time, is breathtaking. Coldiron’s references to the similarly eerie and poignant album which inspired this work are not only accessible to those familiar with Florence + the Machine’s work, but also to those who appreciate spectral narratives of fraught love. Part of the power in Coldiron’s pervasive use of narration, imagery and character suffused with carnality is it’s deliberate anchoring: even while the reader is traversing text that often feels boundary-less, one can be anchored in the somatic sensual.

In the final section, the reader is left with a deeply poignant scene where Corisande and Amelia finally witness one another across the limitations of time and space. Coldiron writes: “She clasps her hands across her beating heart. She has grown old, I see, her hair gray and her eyes netted with decades of smiles, but she knows me. She knows the creature and the memory, all of me.” The totality of feeling between the two main lovers, it’s resistive ability to transcend time and space, as well as the borders between life and death mark this novella as a gorgeous composition on themes in Florence and the Machine’s “Ceremonials”. The novella offers us the space to properly process the nonlinear paths of grief and trauma amidst the persistent resilience of young queer love, and to do so with the sensuous intentionality of musical ceremony.