by MEGAN SWARTZFAGER

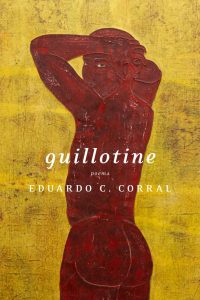

Eduardo C. Corral, Guillotine (Graywolf, 2020), pp. 72.

“Welcome / to la cagada,”– or, “the shit”– one undocumented immigrant trekking through unforgiving desert tells himself in award-winning poet Eduardo C. Corral’s second and latest collection of poetry, Guillotine. The collection is deeply concerned with yearning and despair that flourish in the hearts of displaced people, and with the liminal space that is America’s borderlands.

Corral, who is a Hodder Fellow at Princeton University and an instructor in the English MFA program at North Carolina State University, made waves with his first collection Slow Lightning (2012) when he became the first Latino to win the Yale Younger Poets Prize. Guillotine was longlisted for the 2020 National Book Award for Poetry.

Guillotine, donning the skin of undocumented immigrants from Mexico and border patrol agents, makes its way painfully but relentlessly across desert landscapes that eat away at characters’ bodyminds. This term, whose modern sense is given to us by disability studies, is crucial to an understanding of this collection, as Corral reminds us over and over again that there is no divorcing pain of body from pain of mind and spirit. In “poem name,” for instance, the narrator fights an animal made of hunger and thirst by “hurl[ing] my memories at it. Your laughter is now / snagged / on its fangs. / Your pain / now breathes inside its lungs.” The collection’s narrators experience suffering of body and of mind in nearly identical ways. Emotional yearning parallels physical hunger just as the sting of betrayal echoes the pricks of cactus spines. The very land is hostile to body and spirit as a single entity:

Yesterday, I woke to ants crawling

over my body

to ants crawling

over

the body on the cross around my neck.

Here, we see how the borderlands attack body and spirit— represented by Christ on the cross—simultaneously and via the same avenues, demonstrating the entanglement of body and mind, especially in situations of severe trauma.

The collection’s liberal use of Spanish as a means of establishing the experiences of otherization and distance from home and family furthers and deepens the depictions of its narrators’ suffering. “The sky isn’t blue. / It’s azul. Saguaros / are triste, not curious,” one speaker tells us. Though “blue” and “azul” are synonymous, it is clear here that they do not mean the same thing to the speaker. “Azul” is loaded with childhood memories, with the color of the sky in the home our narrator has left behind, or with the jewelry worn by a lover who spurned him.

The juxtaposition of “triste”—or, sad—and “curious,” though, is even more interesting. These words are decidedly not synonymous, and this reveals a great deal about the narrator’s feelings of estrangement. Perhaps the English speakers he has encountered describe saguaros as curious because they do not feel the loneliness and distance the cacti represent in the way the narrator does. Perhaps the narrator’s associations with the landscape are as irreconcilable with assimilation to English-speaking America as the words “triste” and “curious” themselves are.

In “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel,” the speaker, dying so slowly that he says, “Apá, dying is boring. To pass las horas, / I carve / our last name / all over my body.” Here, the speaker addresses a deceased father from the “Home of the Whopper,” a land that wants him dead. “I stuff English / into my mouth, spit out chingaderas. / Have it your way,” he tells America. The narrator has an unbearable grasp on the pressure to assimilate, but he resists this pressure with his very flesh. He carves his father’s name into his flesh so that his identity will not be lost in life or in his fast-approaching death. Even his bitter shout for America to “have it your way,” is resistant. His bodymind rebels against a tongue that is not his own, and the English he stuffs into his mouth spills out in vulgar Spanglish.

The collection is heart-wrenching and brutal in its exploration of identity, love, and loss; but it is punctuated with tongue-in-cheek humor. “If you think I look good naked / wait until you see me dead,” one narrator seems to say through a grimace. This complexity of emotional register makes the horrors of self-harm, social violence, starvation, violence, and unrequited love all the more painful, but it also goes a long way toward humanizing the collection’s subject-narrators. There’s no exploitation, no torture porn, here. Suffering is something that happens to, is done to, complex and fully realized people as a result of their interactions with human and institutional actors.

In terms of form, Corral experiments just enough to keep the reader guessing—and to keep from becoming too traditional. This is almost always effective: text snakes back and forth across pages like a winding river or the path of a stalking coyote, and conflicting emotions fight for the reader’s attention. The only significant formal shortcoming appears in the middle “Testaments Scratched into a Water Station Barrel,” a section that constitutes roughly the first half of the collection. One page, a jumble of Spanish and English text in the style of bathroom-stall graffiti, takes what is perhaps too much advantage of the variety of fonts that modern typesetting allows. Though the snippets of text themselves are effective—they include calls to “make Arizona great again,” threats of ICE’s approach addressed to “wetbacks,” and statements like “I ♥ brown A$$” and “chinga tu madre gringo”—the typography is jarringly inauthentic. I shudder to use that clumsiest of words, but the shading, font-mixing, blur effects, and digital icons sterilize a poetic expression that could be much more compelling if handwritten.

That minor complaint aside, however, Guillotine was certainly longlisted for the 2020 National Book Award for poetry for a reason. The text is a rich exploration of the relationship between body and mind in an environment that is both socially and physically hostile. With this collection, Corral empathically demonstrates the entanglement of mind and body by showcasing the spectrum of cruelties and misfortunes that terrorize undocumented immigrants who have newly arrived in the U.S. The totality of the damage done only makes sense through the messy, knotted framework of the bodymind.