by JAMIE WATSON

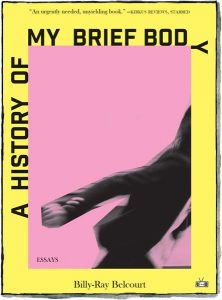

Billy-Ray Belcourt, A History of My Brief Body (Two Dollar Radio, 2020), pp. 142.

What does it mean to have a brief body, to wonder when one will truly feel here, now? How much history can a body carry within it? What are the boundaries of a body?

Billy-Ray Belcourt’s personal essay collection A History of My Brief Body is an insightful exploration of language, embodiment, settler colonialism, and academia. But describing it as such makes it seem impersonal and clinical when it is anything but. Much like Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider, Belcourt’s A History of My Brief Body interrogates systems of power and institutionalized prejudice, takes joy in sensual pleasure, and hopes for community across margins of difference. Belcourt writes, “In this book, I track that un-Canadian and otherworldly activity, that desire to love at all costs, by way of the theoretical site that is my personal history and the world as it presents itself to me with bloodied hands.” Belcourt argues that a nation is constituted and reconstituted in personal history and persistently in hope of anti-racist, anti-settler-colonialist progress. He enacts life writing as activism, showing how personal narrative and self-reflections can lead to larger insights about issues like settler colonialism, heteronormativity, and prejudice, both inside and outside of academia.

Billy-Ray Belcourt was a 2016 Rhodes scholar and earned his PhD from the University of Alberta. He now serves as an Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia. Belcourt is also a member of the Driftpile Cree Nation in Alberta, Canada. For Belcourt, one’s personal life is inextricable from one’s professional life. Belcourt’s experiences as a member of his First Nations tribe inform his academic work; and his research shapes his personal life on and off the Reservation. In the collection, he often code switches between academic jargon, First Nations terminology, literary theory, and queer colloquialisms, binding these languages together in poetic prose.

Belcourt offers gut-wrenching insight into settler colonialism in Canada, describing government-enabled and institutionalized racism from its most brutal to its most subtle. And he writes of the pain that arises from both anger and compassion. Belcourt writes:

I have to at least marginally play dead to white anger and white sovereignty and white hunger and white forgiveness and white innocence. If one is alive to all these rabid emotions all the time, one experiences the world as though it were nothing but TV static. It’s a sedative, so indifference is no armor.

A History begins with a letter to Belcourt’s grandmother; the specificity of address conveys to the reader that they may not understand everything. The text is not meant to be easily digested or synthesized because Belcourt does not attempt to coddle and comfort white readers. Here, Belcourt attempts to articulate his complex attitude toward the relationships between his own identity as a thoughtful, loving young man and one who has been continually injured by institutionalized racism, whiteness, and white people. Belcourt depicts his experience as a struggle to forgive “white anger,” “white sovereignty” and “white hunger.” But he also acknowledges the possibility for “white innocence” while also honoring his history, body, and understandable fear in voicing this mix of feelings. He gives space for this type of messiness. At the heart of Belcourt’s book is complexity, conflict, and hope for what Belcourt describes as utopia.

A History of my Brief Body is a challenging conversation between author and reader—and a conversation that is well worth undertaking. As a reader, I was challenged to confront both the gaps in my historical knowledge and the gaps in my creative expectations. His blending of poetry, memoir, personal essay, and academic writing breaks generic rules, and shows that the rules ought to be broken. There is lived pain in these pages, pain that many of us who identify as white will never have to experience. But to read Belcourt’s exploration of language, desire, and community is a gift.