by MINDY BUCHANAN-KING

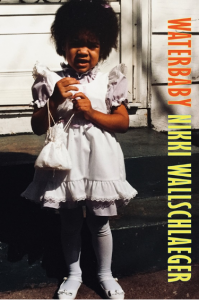

Nikki Wallschlaeger, Waterbaby (Copper Canyon Press, 2021).

Reading Nikki Wallschlaeger’s third collection of writing is an immersive experience. The title, Waterbaby, elicits a sense of submersion, and the theme of water winds and slips between the pages. Wallschlaeger’s words flow across the themes of motherhood, ancestry, politics, and capitalism, all of which are portrayed as being issues of the body, the mind, and the spirit. Wallschlaeger is a Black poet residing in Wisconsin and is the author of a graphic chapbook I Hate Telling You How I Really Feel. Her work has been featured in such publications as The Nation, American Poetry Review, Kenyon Review, and Poetry. She is also the author of an artist book entitled “Operation USA.” In Waterbaby, Wallschlaeger departs from the sheltering spaces explored in her previous poetry collections, Houses and Crawlspace, to submerge herself and her reader into a tributary of powerful, voluminous images that feel unbound and expansive.

Waterbaby is a haunting read, with Wallschlaeger’s expressions full of Black bodies suppressed. In “All Kinds of Fires Inside Our Heads,” she equates “[t]he number of bodies I have /…to the number of / gurney transfers that are / televised.” This collection is not the work of an individual. Rather, it is a commingling of words echoing forth from the depths of the past, mediated through Wallschlaeger’s writing. Waterbaby seems to resurrect the dead, bearing forth the historical truth. Wallschlaeger’s (physical and figurative) body seems to be bound by a birth cord to a history still pulsating with life; she finds she can “splash unapologetic / on how deep this umbilical gets.” The living Black body is portrayed as entangled with the spirits of yesterday, as in “Nobody Special,” wherein Wallschlaeger writes of “seamstresses weaving our chains” while wondering “I don’t know when the spirits get in.” In “Middle Passage Messaging Service,” Wallschlaeger pens a free-flow poem capturing the movement of enslaved bodies trodden beneath the depths of the plantation ground—those “towers of excess” that mutilate and kill—and also of voices continuously choked off today, a “Black code” of language silenced within the depths and deprivations of contemporary archives that still seek to not tell the stories of struggle.

Wallschlaeger uses Waterbaby as a conduit of judgment. She calls out canonical works, for example, that continue to weigh down and suppress othered bodies. In her short-story section, Wallschlaeger holds in “underground contempt” the works of Shakespeare and William Carlos Williams. Wallschlaeger’s imagined discussion with the titular writer in “Robert Frost” is particularly compelling; she tells him of the local myths of bodies drowned in the “frozen solid” lakes that Frost wants to construct as only sublime. Wallschlaeger addresses each dead author directly as artists who fail in their works to acknowledge the lives and experiences of the marginalized. They all, she says, wind up reifying politicians and their power structures of subjugation. By extension, so too does Wallschlaeger condemn readers of these dead but lionized men as failing to acknowledge the problematic nature of a “canon” that swamps the voices of the suppressed.

Wallschlaeger also uses her collection to condemn political structures, especially that of capitalism. She names one of her poems “I’d Come Back from the Grave to Celebrate the End of Capitalism.” In another piece titled “American Children,” gone are the days of chalk-drawings upon concrete that materialize the imaginings of flora and fauna. Instead, concrete becomes a canvas for children’s Americanized realities, chalk becoming the medium for “outlining…bodies on the ground” (55). Wallschlaeger is clear in her message: A nation’s love of capitalism will not only rob children of their idyllic childhood fantasies, but it will also break Black bodies on the streets. Capitalism will do nothing but violently destroy familial roots, the heartbreak of which is woven within works like “Mother of Thousands” and “100-Year Flood.” These poems of motherhood speak to the deep tethering of the body of a Black woman to not just the body of her child but also to the physical, economic, and political bodies that heave against her and endeavor to crush her. It is not nature that Wallschlaeger’s body struggles against—it is not the waves of the ever-present flow of water that pull her under or topple overhead, drowning her out. Rather, it’s the “working shit jobs” that “unsettled her more than a / flood ever could” (27).

Given all of these things that Waterbaby is—all of these entanglements between the self, Blackness, motherhood, language, politics, social and cultural structures, and economics—its publication during the pandemic feels like an encapsulation of our tense and complicated moment. Waterbaby is aware that we are never truly just individuals; we are never just a party of one. For Wallschlaeger, the “self” is a cacophony of the bodies, minds, and voices of those who came before, of those who go ahead, and of those who are forced to survive instead of to thrive. It is haunted and haunting, tired but wide awake, gagged but screaming to be heard.

Mindy Buchanan-King is pursuing her Ph.D. in English Literature at UNC Chapel Hill and is a teaching fellow. Her graduate research is focused on questions of disability and medicine in late 19th-/early 20th-century U.S. literature, the history of “disfigurement,” and representations and interpretations of the World War I facially wounded in wartime medical photography, modern art, prosthetic augmentation, and personal narratives. She is pursuing the graduate certificate in Literature, Medicine, and Culture. Mindy is a contributing editor for Iris: The Art and Literary Journal at UNC, is a co-coordinator of the Furst Forum, and is the recipient of an LSP Teaching Award.