by DEREK WITTEN

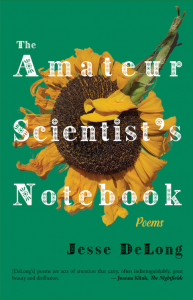

Jesse DeLong, The Amateur Scientist’s Notebook (Baobab Press, 2021).

Anyone who has vaguely intuited an unknown poetic language behind terms like electroweak, phosphorous, chlorofluorocarbons—or even behind the law of gravity- will find a skillful interpreter in Jesse DeLong. His first poetry collection, The Amateur Scientist’s Notebook, sees nature not only through the eye, but also through the microscope, the textbook, and the diagram. What a human being is within the linguistic fields of family, romance, or religion is rubbed against who we are in the language of science; the poetry is the spark produced by this friction: “DNA, disturbed in a sun splotch, carry forward, if you would, / the bright wreckage of us.”

The result of DeLong’s synthesis is hybridized nature poetry. Its route to meaning passes first through scientific formula and law, and only then does it link itself to the spheres we are taught to consider more human: emotion, relationships, love.

A good example of this route is found in a poem entitled “Occurrence of Phosphorous Intermediates in Florets.” The reader’s first encounter feels thoroughly scientific, for the poem is organized into three clean columns: “where observed,” “intermediates,” and “florets, referents of.” Intermediates (I discovered after some googling) refer to a substance produced in the middle of a chemical reaction. It is a necessary mediator, something required to complete the reaction, but produced and consumed along the way.

But the science quickly makes its way to more familiar poetic territory as DeLong injects the mechanical-sounding word, “intermediates,” with life blood. In the context of the poem, the “intermediates” become, rather than chemical compounds, things such as “Irises Uprooted,” “A nail arched from a long finger,” and “Sedum Leafs.” They are not part of a chemical reaction per se; they are part of the larger reactions that occur in the stories of creating, destroying, and reassembling family life. The elements and intermediates set out in the columns are consumed in the histories of the speaker’s parents, only to re-emerge in a later scene between the speaker and his own love in the present.

Here is Delong’s version of a chemical reaction: the speaker’s father digs irises in 1975. The dug earth re-emerges when he “dumped / his eyes like a pile / of earth” on the speaker’s mother. The speaker and his own love, much later, root their hands “in soil / cold as a teabag left / in an empty cup.” In this reaction, the dirt of uprooted irises is an intermediate, something necessary in the chain reaction of generations; something gained and lost and regained, yet still evocative of loss. The line between metaphor and description is thin: does DeLong merely compare family to a chemical reaction, or is the implication that family really is an enormously complex reaction writ large over decades? I am not sure, but the question itself is fruitful.

The book’s reference points are intriguingly eclectic. Formally, DeLong is firmly in the modernist tradition. The poems’ shapes are as unpredictable as those of the natural phenomena he writes about. I thought of Gertrude Stein several times—madly repeated words, floating (or fabricated) punctuation marks, a general sense of restlessness with established patterns. I won’t attempt to reproduce the layout of a middle section of “The Aether Notes”: “(pastpastpresentpresentpastpresentpastpast / presentpastpastpastpresent…” etc.

Or maybe a better reference point is a contemporary like Maggie Nelson, whose quest to create an academic-poetic hybrid maps roughly onto DeLong’s attempt at interbreeding the freshman chemistry lab with a poetics of spirit and desire. The two are also kin in their extended ruminations of a single word until it takes dazzling new shape: Nelson’s Bluets circle round and round the colour blue. For DeLong it is not “bluets” but “florets” that are endless in their significance. The opening, and perhaps the best, poem meditates upon the florets of the sunflower. They re-emerge all over: “A single floret of smoke points onward.” Thoughts “un-floret.” There is “Floret as Phosphorus,” and “Floret as Bird.” None of these phrases will make sense unless you read the collection. If you do read it, they still won’t make sense, quite—but they will place themselves on the evocative, hyper-reactive map DeLong has sketched.

Weirder than the contemporary reference points—weird in a good way—are the book’s more traditional allusions. John Donne, John Milton, and Isaac Newton each pop their heads out of the canon only to be bent quickly into line with DeLong’s idiosyncratic parlance. Isaac Newton is shirtless, moon-eyed, and ditchdigging, curious about the laws of motion not from a mathematical point of view, but from the standpoint of desire:

if the force the girl propels toward carries forward in her mind while at the same time the force she is attracted to continues diverting her, then she will carry both forwards & downwards, both away from him & towards him, suspended in perpetual, bewildering motion.

Milton’s closing lines to Paradise Lost are, similarly, introduced only to be scientifically metamorphosized: “We, hand and hand with wandering steps, and slow. A hologram: our bodies on the shifting pigment. Through light we took this solitary way.” Again, this madcap shift in tone—religious epic to USS Enterprise—will make more sense when you’ve traveled with DeLong along his sensitively scientific path. He earns the weirdness.

The references to Newton and Milton both work, in their own way. They are cute and a bit aware of their own quirkiness, but are also poignant and funny, like a well-delivered indie romance. But the most important traditional reference is to John Donne and his metaphysical poetry. In two poems “On Air & Angels,” the speaker muses, as did Donne, on the possibility of reconciliation between the infinite and the finite. The speaker concludes that this type of reconciliation is in need of some form of half-way point—specifically angels:

Metaphysicians, like himself, believed not in twos, as he was confronted with, but threes. Some celestial, aerial, & material. Some god, angel, & us others. Some infinite, some temporary, & the angels, thank goodness in between.

Angels are intermediates, something half way between the finite and the infinite. Something necessary. Even the chemical reaction between man and God, then, is rendered in DeLong’s fieldguide.

Angels to intermediates is not the only link between DeLong and the metaphysical poets. It is DeLong’s unifying vision of the world’s terrifying but glorious possibility for overlap that struck me as distinctly Donne-like. “Where one is one, & once lost in one. / Where one is once here & there.” DeLong does not succeed in wresting the two unlike images into one like Donne might: but neither does he seem to particularly want to. He is more interested in the complex splintering that occurs when we dare attempt the metaphysical conceit: “How do I locate / myself while simultaneously accounting / for the losses endured to both before & after I, / not the dragonfly but its shed skin…” Every reaction leaves a remainder, and that remainder is DeLong’s subject as much as the reaction itself.

If I haven’t yet made it clear: these poems, like Donne’s, are dense and heady. A floret is never just a floret: it is also a wisp of smoke, and a bird’s feather, and an irresolvable tension between the one and the many. Sometimes the metamorphoses are taken too far. If DeLong has a bad habit, it might be loading a sentence so heavy that the meaning drowns: “Thousands of florets / … so tiny they squander intricacy on light cherished, / smoldering, gold with transparency, canvassing / petal-centers in the borderlines / of hunger.” If you can keep track of everything here you are a better reader than me.

More often, though, it is both possible and worthwhile to trace DeLong’s constant verbal transmigrations. They are filled with unexpected and satisfying recombinations, metaphysical poetry for the 21st century. They’ll make you wish you’d never tossed your high school chemistry textbook. Or make you want to rewrite it.

—

Derek Witten is a second year PhD student at Duke University, where he studies medieval and early modern literature.