by DONAL MACADAM

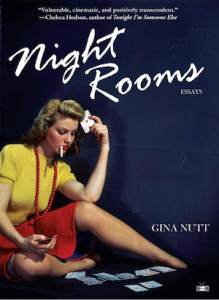

Gina Nutt, Night Rooms (Two Dollar Radio, 2021).

Gina Nutt writes that horror in film is “a reaction, recognition, a response to a call.” Nutt is the author of the poetry collection Wilderness Champion and two chapbooks— “Here Is My Adventure I Call it Alone” and “Ars Herzogica.” Her writing has also been featured in several noteworthy publications, including Cosmonauts Avenue, Ninth Letter, and Joyland. In her first collection of essays, Night Rooms, Nutt, like many of the horror movie references that bind her essays together, issues a call for recognition—a recognition of the anxiety, fear, suffering, and despair that unites people with one another. Night Rooms asks its reader to join the author in a state of transparency, a place of authenticity that bridges the many gaps identified in the collection: that between the everyday sacred and profane; between academic niches and the broader culture; and between one’s public and private selves.

Night Rooms proves challenging to describe in any summative way. While the collection largely explores suffering, grief, and death, Nutt refuses the forms traditional to these themes. It is not elegiac, for instance; instead, each essay offers a prose-poetic amalgam of reflections, anecdotes, news stories, and divergent etymological notes, all of which are threaded together by the canon of horror cinema. In turning to the popular genre, Nutt partially follows Carmen Maria Machado’s acclaimed memoir In the Dream House (2019). However, while Machado uses horror tropes and folk motifs (often horrific ones) to characterize or introduce life events—demonic possession sets the stage for describing life with an unstable and often abusive partner, for example—Nutt’s engagement of horror is anchored in its cinematic manifestations and often serves as an explanatory or reflective resource. The treatment of horror films alongside Nutt’s memories and experiences gives readers the impression that scenes from particular movies have helped her better understand vexing and challenging circumstances. This approach manifests in how she quickly correlates meditations on her “real-life” with often-unintroduced paraphrases of a scene or direct quotes from horror films. Deciphering one from the other is a challenge Nutt leaves primarily up to the reader. In another sense, Night Rooms‘ emphasis on obscure practices and cultural responses surrounding death and grief is reminiscent of Caitlin Doughty’s Smoke Gets in Your Eyes (2015), which focuses on the work of a present-day mortician and American discomfort with and responses to death. Again, Nutt distinguishes herself from Doughty’s more expository approach by treating death and grief in a manner that accepts the ambiguities that are true to her lived experience; uncertainty surrounding death and suffering is more borne than fought against, more embraced than explained. As far as I can tell, much of the impact of Nutt’s collection rests on the open-ended inquiry posed at the end of the first essay: “If we can attach ourselves to art, maybe art can attach itself to us. Do I find the movies or do they find me?” The answer—the latter option, in my reading—is unveiled slowly through how she stages “the movies” as intimately attached to her reconciliation of parts of herself.

Throughout Night Rooms, tension builds and carries through confrontations of binaries—between the sacred and the profane, most obviously. In her opening essays, Nutt recounts events of her childhood that now, through her current vantage point, are identifiable as profanations of sacred symbols, postures, and garb. Describing a second-hand memory of her childhood discovery of a dead mouse as akin to “listening to someone describe a movie [you] can’t remember seeing,” Nutt writes, “Hands cupped as if asking for a communion wafer, I crept into the kitchen from the garage, approached my mother to show her what I found. The mouse was tiny and brown. The mouse was dead.” Nutt expertly captures the unsettling nature of this profanation by filtering the initial sacred referent and its fall through her persistent interpretive framework—horror film. The dead communion mouse raises questions of death, of what intangible reality remains aside from the immediate accidents of physical form, of whether death is a “temporary symptom relieved by waking,” of the possibility of resurrection. For Nutt, the anxiety implicit in these questions creates a sense of “fall[ing]” reminiscent of “movies about dream places,” ones in which the fragility and temporality of life are apparent. Specifically, she cites The Wizard of Oz (1939)—an unexpected entry into the horror canon—in which “a girl [Dorothy] and her dog run from a funnel the sky focused on Kansas,” and later “Dorothy is carried by flying monkeys to a tower where she watches the red sand of her life nearly run out.” The mouse does not issue the same future hope and assurance as the Eucharist does for Christian believers. No more does the aftermath of Dorothy’s time in Oz—Dorothy’s resurrection, so to speak—as told by the 1985 sequel, Return to Oz, resolve into clarity or hope. As Nutt tells us, Dorothy is reintroduced not in the optimistic light of the 1939 film’s end, but rather as she is about to undergo electrotherapy amid her descent into a much darker version of her first fantasy.

In a similar vein, Nutt documents the disorienting experience of wearing a dress from Easter Mass during the “Eveningwear” segment of a children’s beauty pageant. The sacred in this instance is removed from its context and forced to adapt to an otherwise profane setting; she’s not in church, and it’s not Easter. Nutt relocates the Easter dress-turned-pageant eveningwear in a discussion of grotesquerie: children’s false front teeth or “flippers” (in the pageant community), House of Wax‘s (2005) murderous wax figures, pageant participants posing for photographs as “pinup girls,” etc. In a concluding note to her pageant girl essay, Nutt recalls the expanding of a “Carousel Center” mall into “Destiny USA.” The remodel included a “comedy club, a hotel a with swimming pool, an indoor amusement park… [and a] Catholic chapel and religious gift shop [that] took up residence on the mall’s underground floor.” Interestingly, Nutt builds upon the etymology of the mall’s name—”Destiny” as originating from the Latin verb destinare, meaning “to make firm or establish”—with her own interpretation: Destiny as “the inverse of doom […], [a] concept [that] does not discern between luck, mediocrity, and misfortune, only the unseen certainty that fate implies.” Destiny, for Nutt, is ultimately “a more formal, elaborate sounding word for endgame or future.” These definitions act as critical commentary on the mall’s transformation. What in another circumstance or time would have been sacred—a foundation of cultural security with an established telos and eschatological vision—in “Destiny U.S.A” becomes nothing more than a sort of relic of a bygone locale of value. In this way, the mall’s new composition functions like the Easter dress; the referent to the sacred remains, but through its profanation into a sort of faint ancillary of a commercialized structure, it begs the question: how far can we dislocate the sacred before it ceases to function as such?

Nutt’s essays also seamlessly integrate that which is usually relegated to corners of academia or niche literati circles into discussions of popular box office films; this, too, is a confrontation of binaries. In thinking about the acceptability of certain darknesses, a poem of Jenny Zhang is placed in conversation with Tim Burton’s Beetlejuice (1988) and Tobe Hopper’s Poltergeist (1982). By engaging two art forms, Nutt illustrates how Zhang’s sentiment—”Darkness is acceptable and even attractive so long as there is a threshold that is not crossed”—extends beyond readers of POETRY magazine and is visible in the experiences of the family at the center of Poltergeist. The family finds the supernatural activity “fun at first,” but in their obliviousness to the implications of excavating a gravesite, they cross the “threshold” and enter a much more dangerous relationship with darkness. Likewise, Nutt demonstrates how Paul Celan’s “Microliths” and Neil Marshall’s The Descent (2002) both aid in grasping the depths of despair. And Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) may be just as valuable to understanding responses to suffering as Leslie Jamison’s essay “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain.” Nutt’s intentional unification of what otherwise might remain disparate parts of the self is what gives Night Rooms its sense of authenticity. She writes not solely as an academic and not strictly as a horror movie fan. Instead, Nutt remains like us, a multi-dimensional human creature with varied interests and engagements—in other words, she is true to life. Her references to popular culture imbue in her essays moments of recognition commonly shared: fear, anxiety, terror, going to/watching movies, etc. Through her use of varied mediums, each piece becomes infused with a relatable voice, one that isn’t afraid to pull from whatever forms of expression help her respond to or reason with dark moments. Nutt’s writing allows the reader to believe via the recognition in horror that we know her and, by proxy, may also know Zhang, Celan, and Jamison. In this way, Night Rooms becomes, in some sense, a conduit for parasocial relationships. These relationships are enabled by the multi-faceted and cross-generic exploration of shared darkness that extends beyond Nutt and the reader and includes poets, critics, moviegoers, horror characters, and so on.

Moreover, in succinct reflections, Nutt draws back the curtains and collapses the divides between our interior experiences and their public corollaries; more specifically, by shining a light on her own experiences, she interrogates how we respond to pain alone and socially. This internal/external dichotomy persists in the collection and results in subtle truths scattered throughout the text. In one essay, Nutt notes: “Familiarity is a pattern that eclipses the gradual fade, makes it easy to miss.” This revelation comes in light of her recollection of dramatic weight loss due to illness; Nutt writes: “I became too small to fit my clothes but I saw myself in the mirror each day. So I didn’t know what to say the first day of school, when a teacher asked if I’d eaten anything over the summer.” Here, blinded by the darkness of isolation, Nutt only comes to the horrific recognition of what illness has done to her body when an outside source illuminates it. In another instance, remarking on the persistent digital presence of a passed loved one, she reflects: “We are all temporary. We are all eternally cached.” Nutt arrives at this statement when Facebook’s lack of “a bubble [to select] for a death” (as a reason for deactivation) collapses the illusory digital and public perception of life among the deceased. These insights are striking not only because we can recognize that they are true and accurate but also because joining Nutt in dismantling the facades of her experience simultaneously forces us to confront our own often unspoken realities. Encountering a person every day, especially if that person is yourself, does make it harder to notice subtle deteriorations. Digital personas do live on after bodies die. How do we reconcile such peculiarities and conflicts of daily existence? Nutt does not provide a direct answer. But I imagine that the construction of Night Rooms is part of the answer. By Nutt “turning the light on,” so to speak, in her own otherwise dark and isolated “night rooms,” she exposes her own vulnerabilities and struggles, allowing readers to come in and share them in the process.

As far as critiques of Night Rooms go, I do not have many. Some may find Nutt’s unconventional style daunting or a bit challenging to follow, but perhaps this is part of the purpose of Night Rooms. Perhaps this is part of the call to recognition shared by horror films and Night Rooms. Perhaps the darknesses we share don’t have to resolve into clarity, and by naming and recognizing them might be a way to make “a lineage of what lingers,” to “not be afraid anymore.” While I could say much more about Night Rooms, I’ll stop by saying Nutt’s inaugural collection is a worthwhile and engaging read for those interested in the subject matter and willing to wrestle with its treatment of ambiguity and unresolved questions.

—

Donal MacAdam is an English Ph.D. student at Duke University. His research primarily focuses on Renaissance drama, philosophy, and theology.