by COLIN DEKEERSGIETER

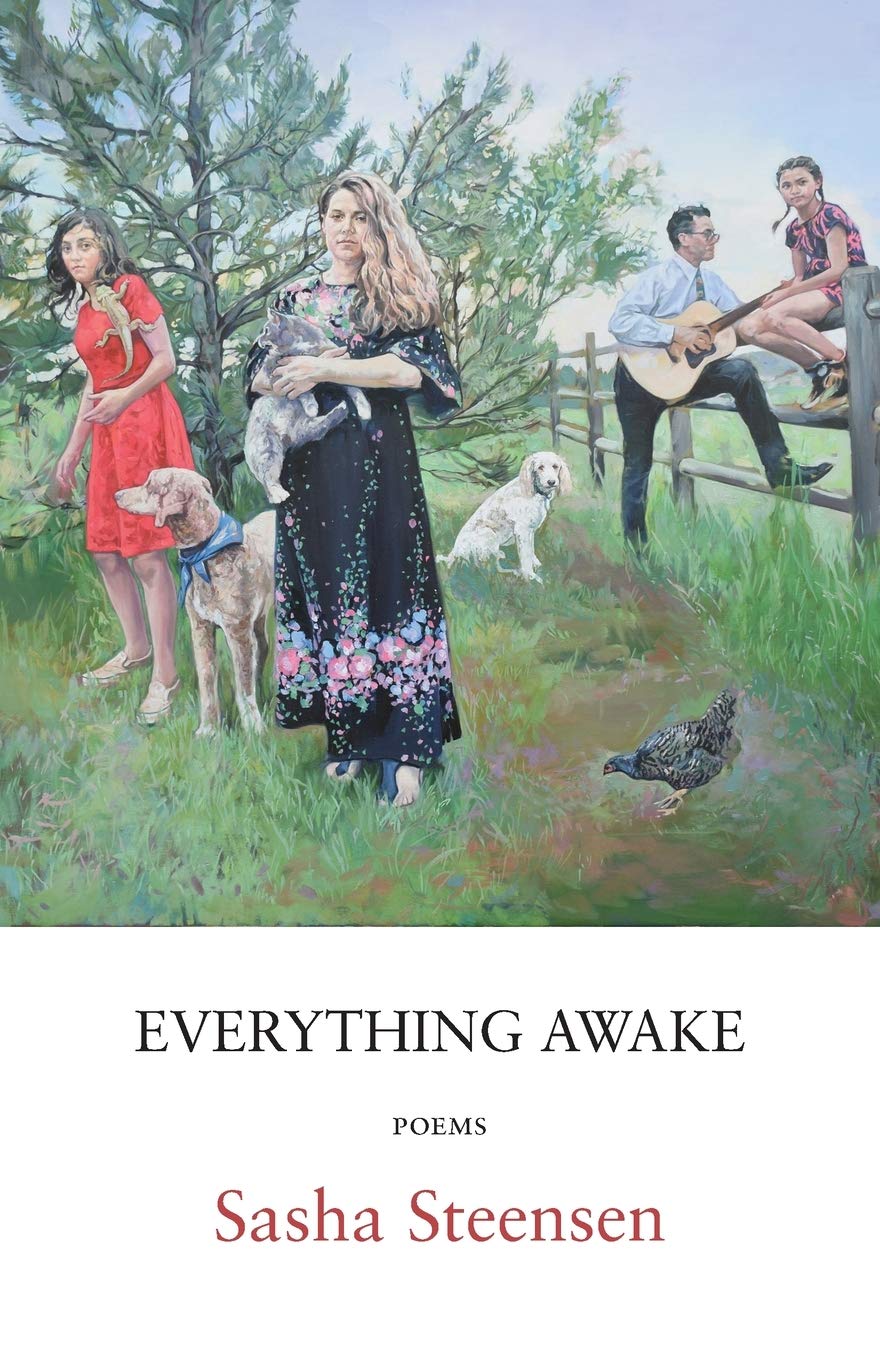

Sasha Steensen, Everything Awake (Shearsman Books, 2020), pp.90.

Sasha Steensen’s Everything Awake is a poetry driven by the vertigo of life’s work, maintaining a legacy begun by Hesiod and continued by — to name a few — Virgil, John Clare, Robert Frost, A.R. Ammons, and Bernadette Mayer. Like the latter, Everything Awake resuscitates bygone notions of the working poet by resisting and confusing definitions of labor. Labor mingles as maternal love, self-care, tending farm, and writing, all couched in fervent aubades and odes to sleep, insomnia, and a life made between. All this living blends through a hypnopoetics that utilizes the liminal knowings within the “ambien ambient daze” of an engaged exhaustion. The admixing of fatigue and work and insomnia and craft blend the hypnopoetic into compositions consisting of two exalted poetic strains, the prophetic and the quotidian.

The Prophetic

According to Pausanias, the Boeotian tradition holds that the invocation which opens Hesiod’s Works and Days was added by a different poet at a later date. If true, Hesiod’s ancient poem would open with a knowledge claim rather than the more traditional humility which defers skill and understanding to the gods: “It was never true that there was only one kind / of strife. There have always / been two on earth.” While more rare in the Greek tradition, opening with an assertive stance was popular among the later Romans. This is evident in the epigraph to Everything Awake, which is by the Roman poet Catullus and ironically plays on the divine invocation but claims that his poetry evolves from skill with meter: “Come, you hendecasyllabics, in force now, / each last one of you, from every quarter.” This type of poetic bravado continued with fits and starts through the Metaphysical Poets (“Busy old fool, unruly sun,” Donne), the Augustans (“Muse, ’t is enough, at length thy labour ends,” Pope), and the Victorians (“O you chorus of indolent reviewers,” (Tennyson)). But it fell out of favor for many in the 20th century. Stream of consciousness writing seemed more apt for the turn to Modernist fragmentation and in many seminal works this fragmentation led to a confidence in style but a deferral of the poet’s active resolve. Given The Waste Land’s (1922) title, Dantean dedication, Sybillic epigraph, the opening line’s direct reference to Chaucer, the reminiscence in the Hofgarten, and the Lithuanian who may or may not be Marie, we have at least seven voices before the ending of its first stanza, most of which aren’t the poet’s per se. Taking a more apt example, Gertrude Stein’s earlier work Tender Buttons (1913) operates differently from Eliot’s varied voices. Rather than ventriloquism we have a singular voice in Stein, a voice who makes non-universal and so mostly unverifiable knowledge claims. Stein’s “claims” are almost always purely indexical, which she admits; the carafe in the book’s opening, she says, “is an arrangement in a system to pointing.” Though it would be wrong to call Stein’s style anything but assertive in its originality, finding actual assertions is difficult. Her resolve is mostly present in style and not content. Perhaps there was a general fear of didacticism in the century’s fractured ethos. But in a contemporary world perhaps more perplexing than Eliot’s and Stein’s, Steensen’s assertions ring true and illuminate our reality while avoiding didacticism.

Steensen’s opening poem sets a tone that balances Roman, hendecasyllabic assertion with Greek prophecy.

The opposite of wakefulness is not sleep.

Neither the day nor the night can be said to speak

without me. I open my mouth and out shines

the horizon. It hums no matter the time.

In these lines we hear no Greek humility and no Eliotic self-effacement via allusion or voicings. Nothing is spuriously indexed. Rather, Steensen makes a knowledge claim which will be proved throughout the work: “Neither the day nor the night can be said to speak / without me.” Coupling this assertion is the poet’s claim to her own large voice, her environment, and the diurnal run of things. In this way, Everything Awake takes on the immense proportions of the epic while remaining grounded in the quotidian. Steensen’s poet mingles with gods and speaks with and for the elements while keeping her feet on the earth. So who can guess at the speaker’s immensity? Who is the prophet speaking on behalf of day and the more contested poetic front, night? Who is it who with Whitmanic immensity robs Nyx?

What’s that, bright

in the dark distance?The night’s nightcap,

I guess.I rest it atop my windy head

and rest.

Who is this speaking but an agrarian Tiresias or a rural Sybil?

If you crush the bergamot heads with your feet

you find your way forward not by seeing.

If you clean the coop with the new broom

you find no room for the mulched leaves.

If you compost everything but meat

you can’t find the accidentally discarded thing.

However parabolic, these hendecasyllabic claims to wisdom are in typical fashion given the meter’s history of poetic claim-staking and self-defense.

As Steensen writes in the cover copy, she was brought to the number eleven by Catullus, whose hendecasyllabic mode was used to defend himself against critics. This tradition of rebuttal is continued through English poetry, with Tennyson’s “Hendecasyllabics” being a seminal counter to his detractors: “O you chorus of indolent reviewers, / Irresponsible, indolent reviewers, / Look, I come to the test, a tiny poem / All composed in a metre of Catullus.” Steensen’s poet is not defending herself from literary critics but, in essence, Hesiod’s two strifes: “one Strife who builds up evil war, / and slaughter,” and “the elder daughter of black Night,” who “pushes the shiftless to work.” The daughter of Night is Hemera, or day. Her name has roots in “burn” and so is linked etymologically to Hestia, the goddess of the right ordering of domesticity whose name also means “burn” (as in the hearth) but also “pass the night” — the two central, paradoxical themes in Steensen’s collection. Steensen’s speaker embodies “The vigil in hypervigilant,” burning the days away in domestic duties and passing the nights awake, guarding herself, her children, and her farm against various types of slaughter with the defense of a hendecasyllabic shield: “Eleven opened up onto an expanse in which I could think about dwelling, in a day, at the foot of a wind-swept mountain, in a family of humans, animals and plants, all of whom needed my care” (Cover copy). Thus the claims of the hendecasyllabic prophet are rooted in the very human need for daily labor and providence.

The Everyday

“And what is life?” asks John Clare. “A busy bustling still repeated dream,” he answers. “And happiness? A bubble on the stream / That in the act of seizing shrinks to nought.” This melancholy approach to life, serene in the face of transience, is a condition among Romanticism’s laboring-poets, which Clare exemplifies. Steensen’s modern genius has more to do than bespeak the serenity of life and when the prophetic strain lies dormant, when day and night do cease to speak, what does the genius hear? Anxiety. To “see not day / uttering speech or night revealing anything / but worry” is to run purpose aground and render insomnia for nought, which is lost time the laborer can’t allow. And so Steensen revises the answer to “What is Life?” by uniting Romantic composure with modern anxieties.

Today is full

of so many things tomorrow won’t be. The sea

smoky, the Murderkill River contaminated

and laundry. It comes to nothing. A relief.

The anxiety-producing potential of a life full of tasks coming to nothing is an integral part of modern life’s social composition. This is our new everyday. The ironic reality Steensen hits on is the fact that our anxiety’s futility is a relief, though this is seldom spoken: being worried with work and stressed on behalf of a destabilizing world is used as proof of a valid existence and we’ll share our concerns so long as “It comes to nothing” in our day-to-day. In Everything Awake the anxieties which remain when the reality of river contamination has no impact on the poet’s livelihood are not fodder for external validation and so are ephemeral as Clare’s happiness. Given the writing’s agrarian setting the work is necessarily concerned with ecology, but in the everyday strain Steensen puts livelihood above all else, existing in the immediate anxieties that drive her work: “I cannot sleep / unless/because / I hear my offspring.” Steensen captures the felt reality of anxiety embroiled in the everyday with both this type of honest content and her hendecasyllabic form.

“I was drawn to the number [eleven], via Catullus because it felt both excessive and insufficient” (Cover copy). The hendecasyllabic renders excessivity because the eleventh syllable takes the American cadence beyond its even tone, beyond decasyllabic comfort, a notion often espoused in support of iambic pentameter. In Steensen, tipping ever beyond pentameter gives the impression of vigilance (of one more thing to do, one more knowledge to (pro)claim) and its vertiginous anxiety. It is the poetic equivalent of seeking the last step in pitch black, not knowing you’ve already arrived. The feeling is further borne out in Steensen’s line breaks.

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty

is and eleven syllable word for sleep

surgery.

Here the oft wished-for passivity of sleep is made excessive through its sudden link to surgery, which implies an anesthetic the hypervigilant no doubt dreads. Steensen heightens these dizzying dichotomies by leaning into branching etymologies at the root of hendecasyllabic, which I take to be at the heart of her work.

Four of Steensen’s six sections are entitled as follows: “Hende,” “Hendes First,” “Hendes Second,” and “Hen Days.” Evident by now, hende(s) refers to eleven through the Greek hendeka, but also to its Germanic and Middle English resonances of “ready to hand,” as in a tool, and “near at hand,” as in an approaching terminus. The tool is her craft, whether exercised with pen, spade, or love. The terminus then, is the death of herself, her brood (in every sense), and the poem (“By me, / I mean the poem”), a death figured in the act of dozing off. But the work holds vigil everywhere and we smirk at the irony when the speaker shouts from the page, “I’m asleep!” Gladly the speaker is awake and the brood is warm as prophecy finds purchase in everyday labor and language and, like Joshua, the poet controls radiance as a means of survival: “One way of staying / awake: Make Catullus’s lines into a sun of sorts / make them perform.”