by PROSPER ALBRIGHT

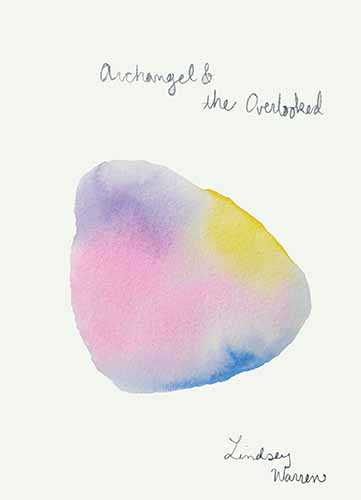

Lindsey Warren, Archangel & The Overlooked (Spuyten Duyvil, 2020), pp. 45.

Like John Keats, Lindsey Warren knows that the task of the poet is to construct a temple in thought, “the wreath’d trellis of a working brain,” and to dedicate it as a “rosy sanctuary” to the goddess of inspiration. Warren also knows that the poet has to leave a “casement” window in the temple open to let “warm Love” in, god of eros, who comes at night to lay with Psyche in her shrine that is the poet’s mind. Invoking this ritual in the first poem of her book Archangel & The Overlooked, Warren shows how “a blue amen opens the window,” admitting an “Archangel” who irradiates this sequence of poems with an erotic absent-presence. Addressing the archangel, Warren writes, “you emerge like an alphabet / curve by curve …/ inside the corners of the room that / I have mapped in pencil / pressing the tip on all presence.” With this the poet signals that writing is a presencing tool, a priestess-rod or stylus for summoning the dead, the lost, the forgotten, and, most importantly in these poems, the angel or goddess that the poem is. Though the book is slim, in Archangel & The Overlooked Warren poignantly explores the limits and possibilities of the poem as an erotic portal, a hermetic window to let in love, or if not love then closure, a self-reflexive openness that makes healing and reconciliation possible in a world outside the text.

Working in the tradition of H.D.’s Helen of Egypt, which navigates the process of recovering from real-world trauma by triaging and treating it in the dreamy twilight of an alternate dimension, Warren’s book is an intimate, visionary sequence that explores the occult power of language to summon healing presence, here in the form of an Archangel, a figure of holy love or lady-of-the-stairs like Dante’s Beatrice, whose distance from the poet is charged with creative energy. The stormy tenderness of address in these poems suggests that the Archangel is a former lover reincarnated by the poet, who tries to re-remember a past relationship, working through its tangles as a way of moving toward a kind of clarifying reunion, if not in body then in spirit. Just as H.D. works through the soul-destroying ruptures of war by exploring the dimensions of an intimacy between Helen and Achilles, half-spirits who try to remember and forget the traumas of their earth-lives inside an otherworldly “Amen, Ammon, or Amun temple,” so too the poet in Archangel & The Overlooked works to “reviv[e]” a lost intimacy in order to “clean the stagnant star,” so that in the penultimate poem,

Absolution places its mouth

against your chest

takes your hand and makes the bed

hair

roots

grow into the sky

walk the wind’s carpet

to where the dream forgets its calloused heels

in the home of light

Of course, these images of healing are not achieved without a cost, not without witnessing the difficulties which build toward them and make catharsis possible. Warren moves across the trajectory of a relationship, registering its bittersweetness, the early days when “sorrows nudge over to make a space / for your glowy toes / that flicker over the floorboards” all the way through the aftermath of loss, when “walls begin to peel / and the blanket on the bed releases its dust” and “the air veined with memories contracts.” In this painful, retrospective contraction, Warren sees “a Tzimtzum that lets in despair,” alluding to the moment of creation as theorized by scholars of Kabbalah, when God withdrew the presence of his totality in order to open an un-godded space for the world to exist. But in terrible absence, both the absences that necessarily perforate language as well as the absence of the other or the lover with which Warren’s poems grapple, the poet manages to find rebirth and transformation:

skin casts off its old scales

the nebula kneeling in the corner

holds its breath

comings and goings in the room

track a spine

midnight shines its knife

through the keyhole

carves from its lightlessness

a rachis

a gasp of plumes

Though abandoned, a lonely galaxy unfurls its iridescent counter-spinning wings. So, too, the poet in her solitude becomes a winged thing, torquing across forms with a protean iridescence. Using the presencing power of poetry and inscription to facilitate her metamorphosis through throes of loss rehearsed, Warren writes, “my body wants to get rid of unused parts / lips go numb / fall into the sink / thighs evaporate,” wondering at the process: “Darling what else is left to morph into.” The magic of Archangel & The Overlooked is to transmute heartbreak into awkward and painful, yet ultimately dazzling regeneration.

Inverting or rhyming with H.D., who writes of the visionary events of “The Flowering of the Rod” that “though it was all on a very grand scale, / yet it was small and intimate,” Warren’s investigations into the difficult stages of an intimacy are lit from behind with a cosmic consequence, as witnessed in the final poem of her book. This poem reveals that the ups and downs catalogued in Archangel & The Overlooked are a shadow of an eternal metaphysical process of destruction and regeneration, “the mint and wreck of structures” that is reflected in the poet’s uneven yet vivid transformations, her hands “smelling of metamorphosis.” Warren ends by clarifying that what her book has demonstrated is a writing process whereby “blood flows back / into another life,” whereby the body shattered by pleasure and loss becomes vast by becoming diffuse, so that the circulatory patterns that uphold life transpire across dimensions, in multiple worlds at once, this world and the world to come, worlds that were and that might be, the human soul spread out across time, the future reaching back to palliate a wounded past.