by KYLAN RICE

Michael McFee, A Long Time To Be Gone (Carnegie Mellon, 2022), pp. 72.

In a notebook from the 1930s, Robert Frost wrote out a recollected line from the poet Archibald MacLeish’s “Ars Poetica”: “A poem shouldn’t mean it should be.” Originally published in 1926, MacLeish’s famous statement was representative of a sentiment shared by many modernist poets, that poems should aspire to the ontological condition of objects. They should, above all, have presence and inertia, an effect of language that resists its reader’s intelligence in the same way that a solid object resists the hand that hefts it, tests its weight, its apple-firmness. Beneath MacLeish’s line, Frost added his own variation, punning on the meaning of “mean”: “A poem shouldn’t mean it should be mean.” The joke is funny and shocking, a sucker-punch. It does much, in my mind, to explain Frost’s own poetics of cruelty, his tendency to write poems that have inviting russet surfaces and dark acid cores, the bitter cyanide in apple-seeds. Frost’s poems are “mean” in that they seem folksy, but actually possess a cunning edge, an impulse toward duplicity and betrayal. Perhaps, as Frost suggests, this is a quality (even an ambition) that all poems share. Aren’t all poems two-faced? Don’t they all rely on the two-faced nature of words, a punning or double-crossing in two or more directions? Meaning is mean like that. It isn’t stable. An apple isn’t just an apple. It is also, among other things, a word, a sound in the mouth, a few scratches of ink on a piece of paper. And words can be twisted, tart.

A poem shouldn’t mean, it should be mean. Meaningfully, mean means more than cruelty. It can also be used to describe something that is low or diminished. That which is mean is meager, humble. Or it could refer to an average, a middle term—the mean in a series. In “The Oven Bird,” Frost describes the song of a “mid-summer and a mid-wood bird,” the sound of which reminds him that summertime is transient. Middleness in the poem—being in the midst, in full presence—is transformed into “a diminished thing” due to a chronic inability to live in the moment, our tendency to anticipate the end. The middle is mean in the sense that it is always being diminished by consciousness, all mentation or mentality a scarcity-mentality. Noon is as none, as no-one, nonce. A word that has no meaning other than its being uttered, once.

If “mean” is read in these terms, what might it mean to “be mean,” and why is it a “must”? What kind of ethics is this? The question that Frost’s bird asks is “what to make of a diminished thing”—what to make of meanness. “Be mean,” as an answer, might name the process of making, if not the most, then something, at least, out of what is left. It might name what it looks like to lay claim to diminishment. Choosing to be a part of it. Life is learning to live with less. To dwell is to die, the way an echo dies inside a cave, not all at once, but like Ravel’s Boléro, our raveled flesh a fanfare thinning into distance.

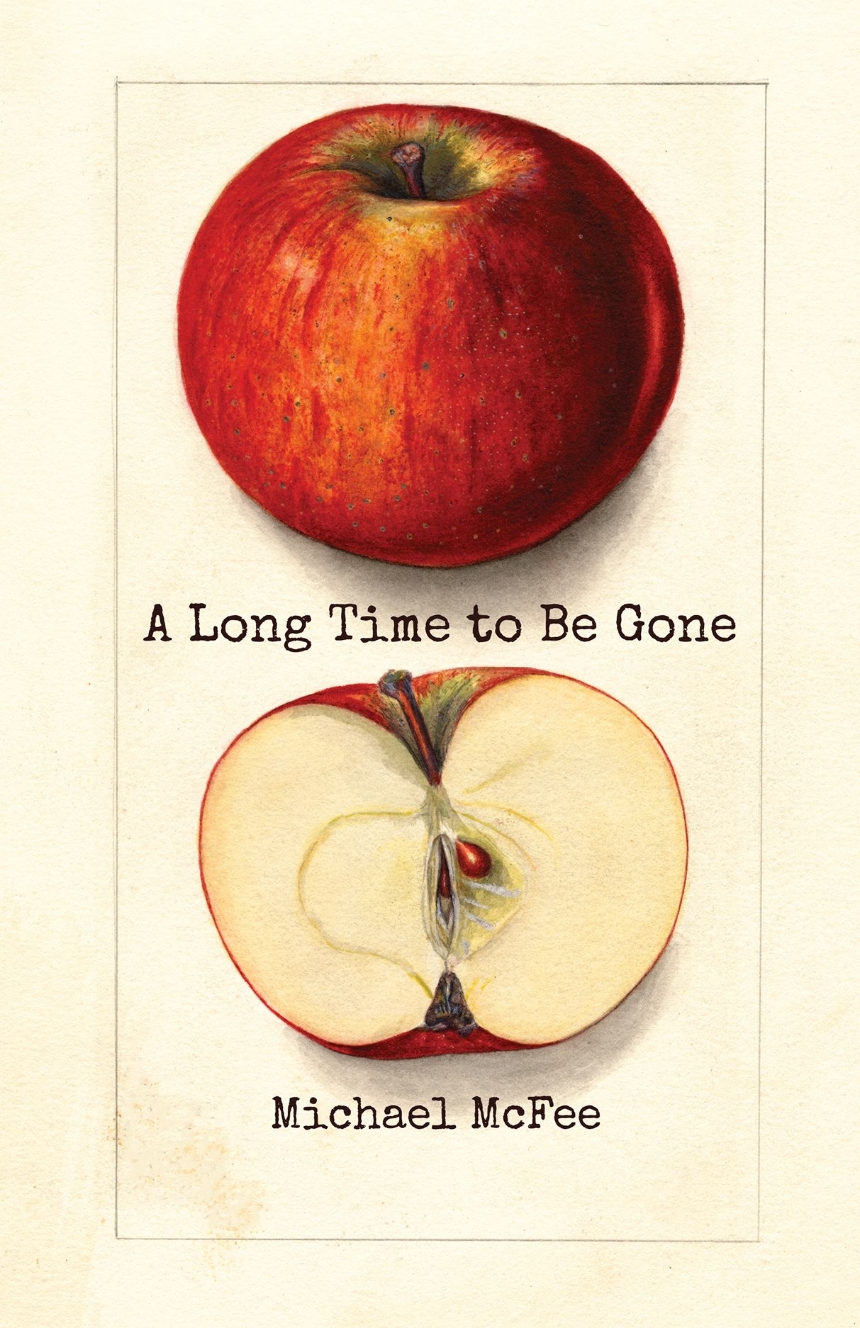

In A Long Time To Be Gone (2022), his poignant tenth full-length, Michael McFee writes poems in the midst of the diminishments that come with age—or what he refers to in one poem as “the dwindles.” In this way, he follows Frost, exploring what it means to be mean, to be gradually reduced as if to ash, a “desiccated stormcloud / of bonegrit” and burning cigarettes that sifts throughout the collection. Also like Frost, many of his poems have an edge. Turn the pages too quickly and they’ll nick a paper cut. In perhaps pithier terms, what I mean is that reading McFee can sometimes be like munching apple-seeds: in some of the poems, there’s a residual taste of bitterness, as of eating something sweet down to the center, the dark pip, which is shaped “like a teardrop.” In other poems, the opposite is true. It’s bitter that there’s little left, a feeling that can sometimes threaten to consume us—but McFee shows how to resist consumption, how to find some succulence in what is unconsumed, the flesh that forms the core. This is the beauty of his work, and it distinguishes him from Frost. The core, although it contains the seeds of bitterness, can still be nourishing. What remains can still be good to eat. McFee offers this insight in “McAfee’s Nonsuch,” the last poem in the volume. The poem performs an ekphrasis on an image of an extinct apple cultivar, which McFee revives to mind by contemplating a watercolor of the fruit painted in 1912 by Mary Daisy Arnold, also the cover-image for the book. There is “none-such” like this superior apple; indeed, it no longer exists. Or rather, it exists only on paper, in two dimensions. And paper’s flatness isn’t nothing. It is minimally thick. Paper says: here—there’s this, at least. And it’s sweeter since it’s scarce.

The edge in McFee’s poetry is the edge that paper has. Indeed, paper and paper products recur throughout the poet’s work. In A Long Time to Be Gone, paper is premonitory of a general burning, a falling to ash. Before that, though, it takes the tight form of a pack of “unlit king-size class A / unfiltered Commanders.” McFee remembers the simple childhood pleasure involved in “pull[ing] the golden strip” around the top of his mother’s packs of Philip Morris cigarettes, which “she’d enjoy all day, / reducing twenty tobacco tubes to ash.” The shared moment, mediated by a cellophane wrapper, is a cherished opportunity for connection between mother and son. But the pleasure has an edge, a bitter aftertaste. It comes “before // the match, the strike, the glow, the sucked-in cheeks, / the smoke blown in my face as I smiled, choked.” As is true for several of the poems in McFee’s book, intimacy in this moment involves an intimation of death, of damage to the lungs. The second part of A Long Time to Be Gone is a sequence of poems that McFee has grouped under the heading “Coronavirus Variations,” specifying that they were written in Spring 2020, during the “first months of the pandemic” in Durham NC, once a major hub for the manufacture of tobacco products. In this sequence, McFee meditates on the threat that we pose to each other, how breath—whether in the form of a breath of smoke or a kiss blown at a social distance—is as much a sign of life as a vector of illness and death. As the poet puts it plainly, “sometimes we infect each other with our breath.” Breath is “word-shaped”; it carries our songs and salutations to other people. And so our words are threats, even when they’re words of affection, kindly spoken. McFee extends this insight to written language, to words on paper, or even spelled out by Scrabble tiles. In “A Sign,” the poet remembers pulling five letters out of a Scrabble bag during a game night at the height of the pandemic: “a C, an O, a V, an I, a D.” The coincidence serves as “a sign the disease could surface anywhere.” It would be easy for this thought to paralyze—and for a while it had that effect, for all of us. But it also sensitizes McFee to the new poignancy of even the smallest gestures of intimacy. Poignant, from the Old French verb poindre, meaning to pierce, to prick. Sweet, but also sharp. Like an acrid mouthful of someone else’s bright-leaf smoke.

A feeling of diminishment dominated the early phases of the pandemic. McFee describes it as a form of “purgatory,” the world turned greyscale, the future rendered ashy and indeterminate: “which afterlife do we wait on the border of?” This netherworldly characterization is important, given the fact that an early poem in A Long Time To Be Gone, presumably written before the pandemic, envisions old age as a long (or maybe all too short) slide down the banks of the river Lethe. Another pre-pandemic poem compares the afterlife to a hospital parking deck, its “stacks of concrete plateaus and tight-turn spirals” guarded by a “dingy angel” in the form of an attendant in a “glass hut” at the exit. As McFee describes it, the spiral structure of the parking deck evokes the stratified topography of the inferno—and also purgatory and paradise—in Dante’s Divine Comedy. When the pandemic hits, the poet seems to wake to a sense that we’re all somehow already dead, together in a purgatory of apartness. The personal problem of death that concerns the first part of A Long Time to Be Gone becomes generalized, communal. Social death distracts the poet from his own slow slide, and in this there’s a bitter balm. A renewed sense of the precarity of life serves to heighten the intensity of what remains. Quoting folk song, the poet reminds us that we “[g]ot a short time to stay here. And a long time to be gone.”

Time is short. It is “wee,” the title of one poem. It is “tiny or teensy,” a word that we stretch to the point of nonsense by adding in an extra syllable: “teeninecy,” the title of another poem in the volume. Time, in other words, is mean. A cruel grinding of the bone to little grit. It is the pebble-shale that pilgrim Dante dislodges on his journey through the underworld, startling the demons and the damned, who suddenly realize, with jealousy, this man has a body still. Here is one who’s able to be borne by gravity. The time-scree we dislodge on our slide “forward and downward” involves a similar bewilderment, and even gratitude. It is the revelation of this book: the body is a pitched slash, a falling virgule. It’s not much, but it’s not nothing. It’s what lets us stay, a paperweight.

For McFee, language—in the mouth, on the page—is resolutely physical. It has substance. It matters and reminds us of our mattered condition, and that our matter means. Throughout A Long Time to Be Gone, the poet plays with words, breaks them apart, tastes them. He uses technical terms from linguistics to describe their “labiodentals” and “velar” consonants, which put me in mind of the physiology of the jaw and throat and tongue, the little cave system that we call a head. McFee reminds us that words are noises, only slightly more refined than cave-grunts, the “hnnnh” that “escapes the old man’s mouth // every time he stands up, or sits, or has to shift”—a “come-groan, a going-away syllable.” Near the end of the collection, McFee reflects on “mutch,” a folk-term used in the North Carolina mountains to refer to the “smoochy inward noise / we make to call animals.” “Mutch” is a word for a non-word; it describes the “near-mute” sound used to communicate when communication is impossible, or when there’s little to say. On the page, it looks like mulch with a cross-bar, like loam with a stone crucifix, the dirt that takes the body back. It’s what we hear before we slash across the narrow sea, “our master mutching us” like dogs, “to rise up and join him / on the other greener side, / to sit, to lie down, to stay.” It is a mean word, below meaning, but tender. A tenderness we are reduced to in being reduced. Our palms held up, mostly blind, mostly deaf. But still with sounds inside our mouth, and in our ears, and even in our skulls, which resonate with hum, with hnnnh, a song.